The Ultimate Guide to Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

.avif)

Leveraged buyouts (LBOs) have gained a largely unwarranted association for excess.

While there have been several high profile failures - notably the bankruptcy of Energy Future Holdings in 2014 - this overlooks the successes, of which there are many.

And while debt combined with hubris is a recipe for disaster, debt combined with solid strategic planning has the potential to generate huge shareholder value.

This article by the team at DealRoom aims to give you a primer on some of the issues surrounding LBOs and why they’re likely to generate even more headlines in the coming years.

What is Leveraged Buyout?

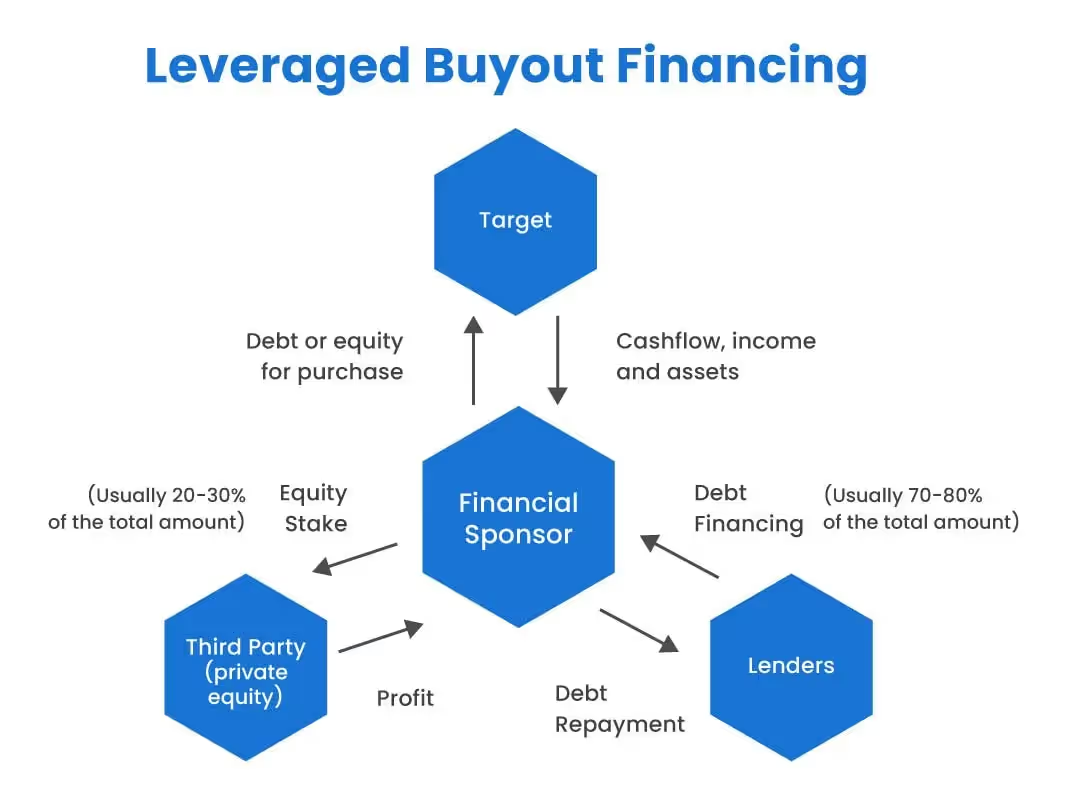

A leveraged buyout is an acquisition whereby the consideration paid by the buyer is primarily composed of third-party debt. The buyer, typically a private equity firm or the company’s current management team, believes that they can extract value from the deal that outweighs the risk taken on to fund the acquisition.

The amount of debt used in LBOs varies, but usually constitutes 70-80% of the total consideration paid. The remainder is paid with the buyer’s equity.

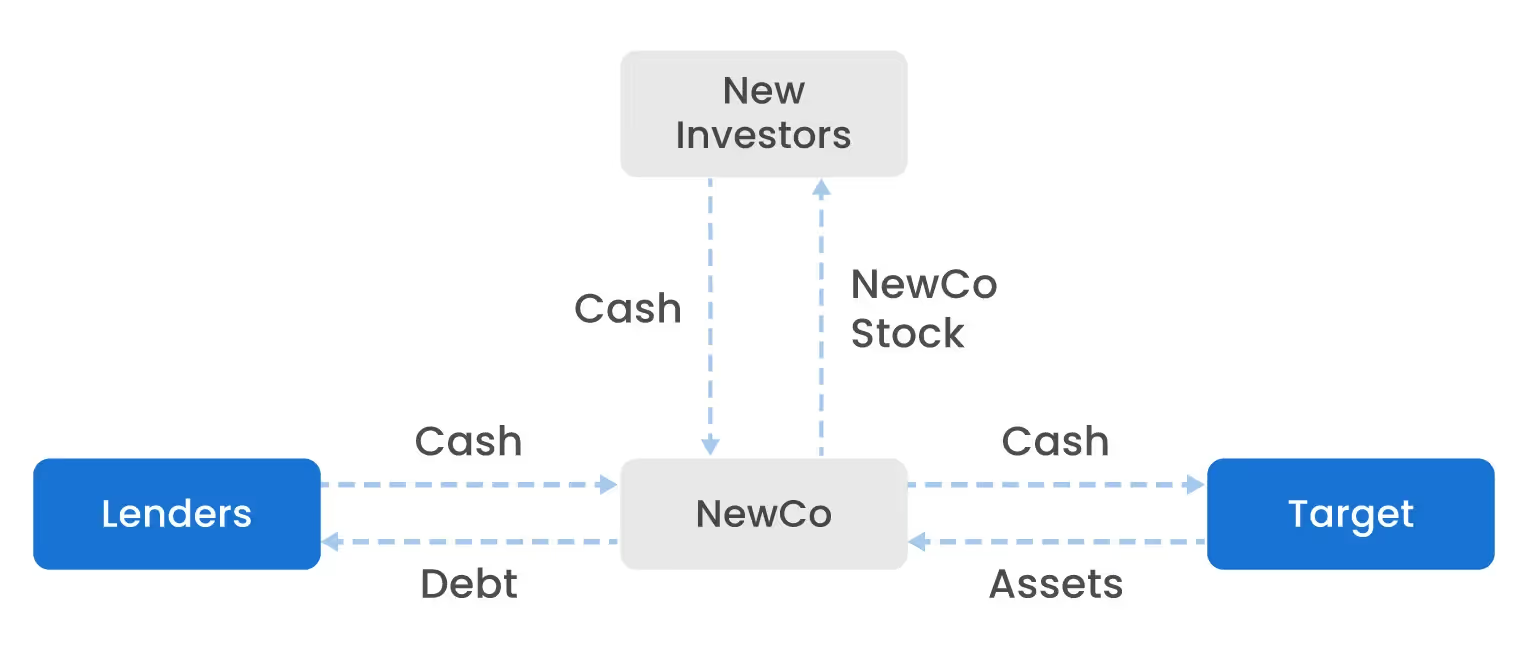

The new investors (e.g. and LBO firm or management of the target) form a new corporation for the purpose of acquiring the target (buyout fund). The target becomes a subsidiary of NewCo, or NewCo and the target can merge. This is further visualised below:

How Does Leveraged Buyout Work?

In an LBO, the acquirer uses significant leverage to fund the deal, using the target company’s assets - rather than those of the buyer - as collateral to acquire the company. The target company’s future cashflows are then used to repay the debt over an agreed period.

A crucial component of the acquirer’s proposition is their management team - for the LBO to make sense to investors, there has to be a strong management team in place.

In broad terms, a typical process runs something like the following:

Create a management team

The process usually starts when a team of industry experts and/or investment bankers come together with the intention of taking over a company in an industry.

Origination

The previous step usually occurs because somebody in the team has insider knowledge of a company and its operations, but not necessarily. In the case that a team has no target company in mind, they will develop a shortlist of companies.

Business Plan

The business acquisition plan developed by the team will focus on how the cash flows being generated by the company will pay down the (usually high) interest, and how the new management team will extract more value than the incumbents.

Funding

With a team and a business plan in hand, the challenge is now to gain funding. LBOS are typically funded by bonds and private notes, but can also use mezzanine financing, bank financing, and on occasion, seller financing.

Due diligence

Before making the formal approach to acquire the firm, the management team will prepare itself for the lengthy due diligence involved in an LBO, using technology to prepare the acquisition phase.

Why do Leveraged Buyouts Happen?

Although LBOs have often taken on a reputation as being a reckless form of financing transactions, the logic behind them is sound. They enable competent management teams with strong industry experience and convincing business plans to take over companies without having the financial resources to do so.

How LBOs create value:

Higher ROI: With less money upfront, in theory the LBO leads to a higher return on income than investments where they use their own capital.

Access to more deals: More capital, means more access to deals for the buyout team proposing the LBO.

Tax advantages: Because the deal involves the company itself taking on more debt, there are usually considerable tax advantages associated with LBOs.

Improved business plan: In theory, if not always in practice, the LBO should put expert managers with excellent business plans in charge of companies for better results.

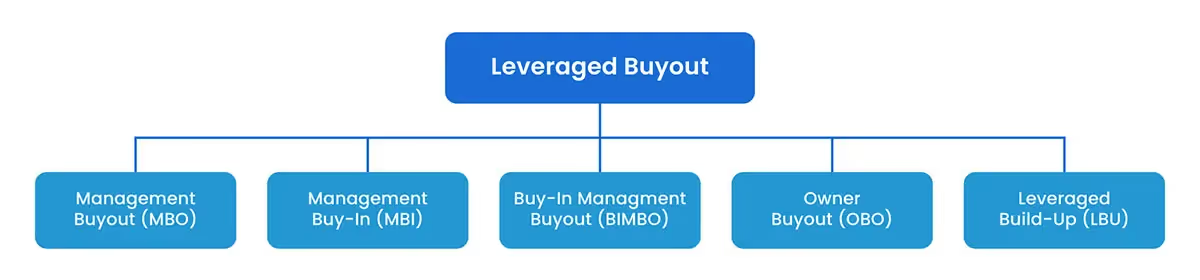

Types of Leveraged Buyout

There are 5 generally recognized types of buyouts. These are as follows:

MBO (Management Buyout or “LMBO: Leveraged Management Buyout”)

A Management Buyout occurs when the current management of a company acquires it, often using outside financing (hence, LMBO (Leveraged Management Buyout). There is likely to be an explosion of MBOs in the next decade as those in the Baby Boomer generation all reach retirement age and begin ceding control of their businesses. MBOs and LMBOs offer the management teams in place an opportunity to takeover these businesses, giving the owners the exit they desire.

MBI: (Management Buy-In or “LMBI: Leveraged Management Buy-In)

A Manageament Buy-In occurs when a management team from outside the company acquires the funds (often through leverage, hence the expression ‘Leveraged Management Buy-In) to acquire the company and become its new management. The differentiating aspect here is that the management is all from outside the company, and have probably identified an opportunity to extract more value from the company than the existing management team.

BIMBO: (Buy-In Managment Buyout)

A Buy-In Management Buyout occurs when existing management (“Buy-in”) join forces with outside outside management (“Buyout”) to acquire the company that they manage. The motive behind any BIMBO is to leverage the best of the company’s current management capabilities, while also adding new management to the team to bring in fresh expertise (and importantly, funding). As with any LBO, the collateral of the company is used to pay for the transaction.

OBO: (Owner Buyout)

An Owner Buyout is a less common form of the LBO, whereby the owner manages to keep control of a minority stake in the business after the transaction has closed. The first step of an OBO is for the outside investor - normally a private equity firm - to acquire the company using a special buyout vehicle (NewCo). The second and concluding step is for the original buyer to acquire part of the NewCo, thereby retaining minority control over their original company, enabling everyone involved in the deal to avail of certain tax benefits specific to this kind of transaction.

LBU: (Leveraged Buildup)

A Leveraged Buildup is considered the same as a portfolio plan scenario (see below), whereby a private investor uses a leveraged investment to acquire more companies in the hope of extracting synergies from them. This is a highly risky strategy. In addition to counting on the synergies being realized – always far from a certainty – this also has to be achieved with higher interest rates, making it something of a double gamble.

Why not check out: 10 of the Most Famous Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs) in History

LBO Scenarios

There are four generally accepted LBO scenarios, that drive LBOs. These are as follows:

Repackaging Plan

The repackaging plan is the logic that underpins most private equity funds. The logic here is for a private equity fund to use leverage to take a currently public company private. As a rule, the public company in question will have underperformed their industry for a while, and its investment ratios (especially its PE Ratio) will naturally make it a target for outside investors.

Depending on the private equity fund’s strategy, and the performance of the company acquired, the plan is usually to ‘repackage’ the company, and relist it after a few years out of the public spotlight. In the intervening period, it usually makes a series of changes in strategy, technology, and personnel. A well-known company which has undergone a repackaging plan on at least two occasions is the fast food giant Burger King.

Split-up Plan

A split-up plan, sometimes given the far less enticing name ‘a slash and burn plan’, occurs when outside buyer realize that a company is undervalued in its current guise, and its component parts would generate more value through a sell off. This is most common with conglomerates, whose component parts might be in separate industry sectors, reducing strategic focus, and ultimately destroying value. On seeing this, outside management would acquire the firm and begin selling off the components at a combined price higher than the acquisition price.

Portfolio Plan

A portfolio plan is another common private equity-led situation, whereby a management team from outside the company foresees significant synergies inherent in acquiring the company and merging it with a company already under their control. For obvious reasons, this is risky: Synergies are often far harder to extract from transactions than investors’ narratives let them believe. Nevertheless, this remains one of the most popular motives for LBOs.

Saviour Plan

In a saviour plan, the management team of a financially distressed company, usually in conjunction with its employees, acquires a loan to takeover the company, hoping to bring it back to stability. Of all the LBO scenarios, this is undoubtedly the most risky. The question that naturally arises is: If the management team is capable of bringing the company back to stability, why hasn’t it done so before now? If there are clear strategic benefits to the management team taking full control (for example, being unhindered by current shareholders who have taken the company in a damaging direction), then the deal stands to be a success.

Critical Success Factors for Leveraged Buyouts

Like any acquisition, the success of an LBO depends on a combination of internal and external factors. For LBOs, these success factors tend to fall into one of the following:

1. Market growth

The case of Energy Future Holdings shows that even an LBO with a world-class management team at the helm is hostage to what happens in the wider market. Most of the high profile failures in LBOs have been a result of markets significantly underperforming the projections inherent in the buyers’ calculations.

2. Cash generating ability

The larger the debt, the larger the interest payments. The aim of an LBO is to generate enough cash to turn debt into equity. Hence, the reason that cash generative businesses such as FMCGs tend to be so popular with private equity companies undertaking LBOs.

3. Operational Improvements

A thread running through all LBOs is that the buyers believe they can make operational improvements to the target company that will generate more cash flow and ultimately, increase the company’s value. This is already a specialty of private equity companies, explaining why LBOs are so popular with them.

4. Management Expertise

Binding all of the critical success factors together is a strong management team. They are firstly responsible for putting together a strategic plan that shows creditors where value will be extracted from the deal. Then, once funds are secured, they will then be responsible for implementing that plan.

Steps involved in an LBO

Details of the steps involved in an LBO will vary on a company by company and industry by industry basis but will typically follow a pattern similar to that outlined below:

Step 1 - The buyer identifies a company that it believes generates enough cash to warrant an LBO. Cash is a key component here. If the business isn’t generating cash, it is unlikely to be targeted by LBO buyers.

Step 2 - The buyer conducts a thorough valuation of the company, typically using conservative growth figures, to show its funders, as well as providing it with a reference value when making a bid for the company.

Step 3 - A crucial differentiator of the valuation for LBOs is that the creditor (usually referred to as the ‘deal sponsor’) will be provided with an IRR for their debt - the expected return on the capital that they provide to fund the deal.

Step 4 - Most buyers will create a strategic plan - showing where operational improvements can be made - before approaching funders. Doing this now rather than later strengthens the pitch with funders, clearly showing them where value will be extracted.

Step 5 - Funds secured, the buyer makes a bid for the company. This can sometimes be hostile - i.e. the current company leadership does not want to sell - a possible issue that buyers like to anticipate in advance and include in their calculations.

Exit opportunities in an LBO

The intention for buyers undertaking LBOs is not value creation for the sake of it.

Rather, they aim to exit the target company at a higher value multiple than that at which they entered within a predefined period of time.

The exit opportunities open to them will depend on how well they have implemented their strategic plan, and as always, the condition of the market at the time of the sale.

Exit strategies in LBOs include:

An IPO

Listing the company on a public index and exiting through the sale of equity may be possible depending on where equity markets are in their cycle.

Strategic sale

A common exit route for companies is through finding a comparable company in the same industry and selling the business to them.

Financial sale

The company could be sold to another private equity company who believes that it can extract even more value from a new strategic plan.

Advantages of LBOs

- Allows competent managers to take control and generate value for companies they otherwise could not afford.

- The high debt used in LBOs usually endows them with tax advantages over cash acquisitions.

- For buyers (i.e., those using third-party debt), there is huge value generation potential on the equity invested in the deal.

Disadvantages of LBOs

- Saddling the target company with a significant debt pile has the potential to hinder its growth rather than turbocharge it

- Connected to the above point, the focus on repaying interest may encourage the company to underinvest in capital, R&D, etc.

- The fact that the management team have so little financial exposure to the downside risks may create an agency problem for deal sponsors.

Examples of Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

Blackstone’s acquisition of Hilton Hotels in 2007

Sometimes good management can mitigate unprecedented market turbulence. Just before the global financial crisis kicked in, Blackstone Group paid $26 billion for Hilton Hotels, using just $5.5 billion (i.e. about 21%) of its own funds. Blackstone eventually yielded $14 billion on the deal from a staged exit, almost tripling its initial investment.

KKR’s acquisition of Safeway in 1986

KKR implemented a strategic plan for the takeover of Safeway in 1986 that involved the closure of underperforming stores and divesting others. They paid just $129 million in a deal valued at $5.5 billion. Value creation in the deal was aided by the fact that Safeway’s management agreed to the deal, ensuring KKR did not have to overpay. Just four years later, in 1990, they exited, yielding a profit of $7.2 billion.

Malcolm Glazer’s acquisition of Manchester United in 2003

Tampa Bay Buccaneers owner Malcolm Glazer spotted the value in English football club Manchester United in 2003 well before its then owners. Glazer acquired the club using £275 million (approximately $400 million), using the club’s assets as collateral. A financial master stroke, albeit one that didn’t endear Gladwell to the club’s fanbase. In 2012, the club listed on the NYSE. In June 2021, its market capitalisation stands at $2.25 billion.

Conclusion

Leveraged buyouts are an excellent way for competent management teams with strong strategic plans to take over underperforming companies.

Although they have gained a negative press due to a number of high profile failures, this overlooks the value created for buyers and sponsors through ensuring that cash generative companies fulfil their potential.

Get your M&A process in order. Use DealRoom as a single source of truth and align your team.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)