9 Business Valuation Methods: What's Your Company's Value?

.avif)

Whether you’re on the buy-side or sell-side, the ability to value a company accurately is critical. The most successful investors are those who consistently identify what an asset is truly worth. While integration can create additional value after a deal closes, paying the right price upfront lays the strongest foundation for long-term success.

What is Business Valuation?

Business Valuation, or Company Valuation, is the process by which the economic value of a business, whether a large or small business, is calculated. The purpose of knowing the business’s value is to find the intrinsic value of the entire company - its value from an objective perspective. Valuations are mostly used by investors, business owners, and intermediaries such as investment bankers who are seeking to accurately value the company’s equity for some form of investment.

Although business valuations are mostly used to value a company’s equity for some form of investment, it isn’t the only reason to have an understanding of a company’s value. A company is not unlike most other long-term assets in that it’s useful to have a handle on how much it’s worth. Being in an informed position at all times enables the company’s owners to understand what their options are, how to react in different business situations, and how their company’s valuation fits into the bigger picture.

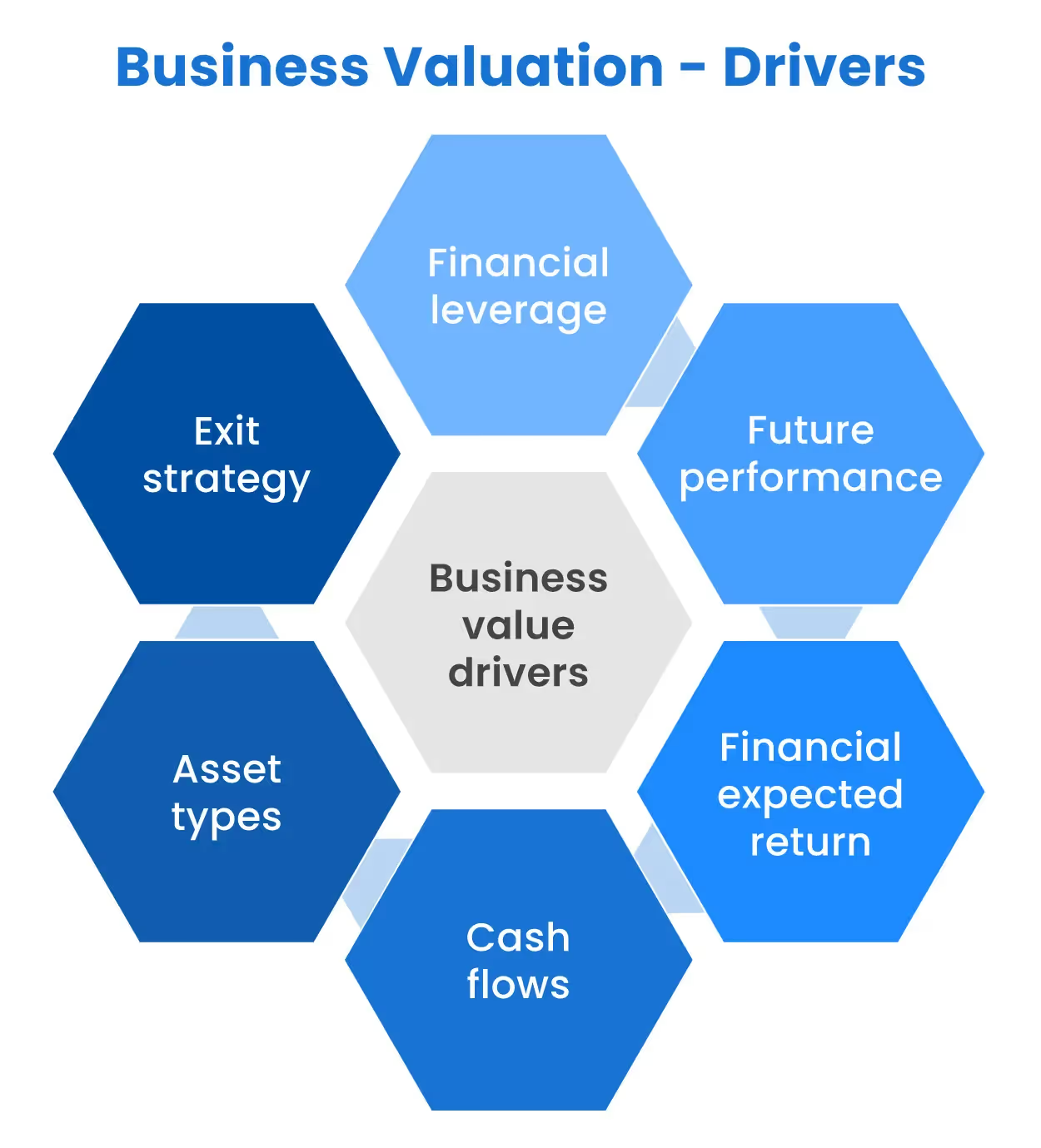

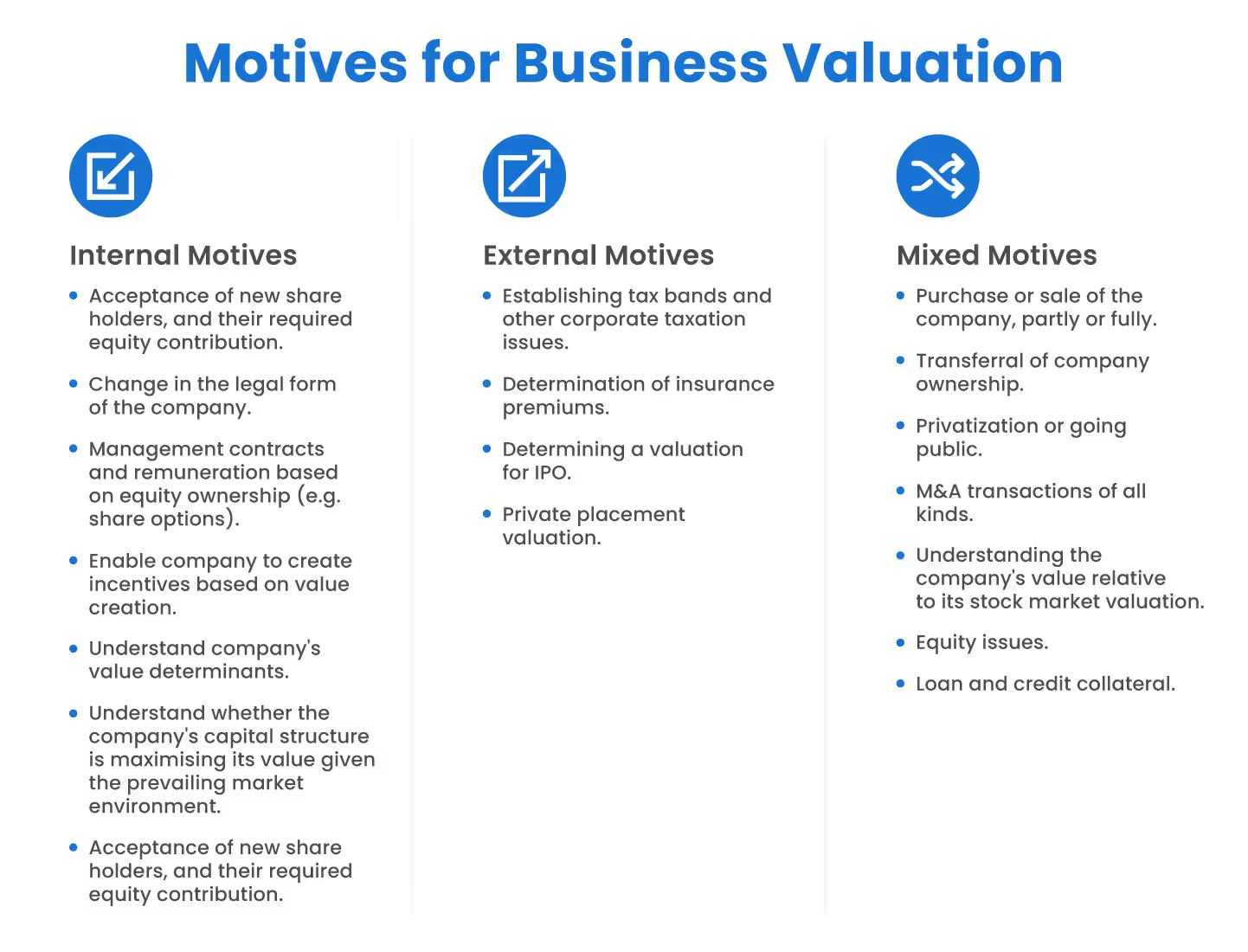

The objectives for valuing a business can be divided into internal motives, external motives, and mixed motives (a combination of internal and external motives).

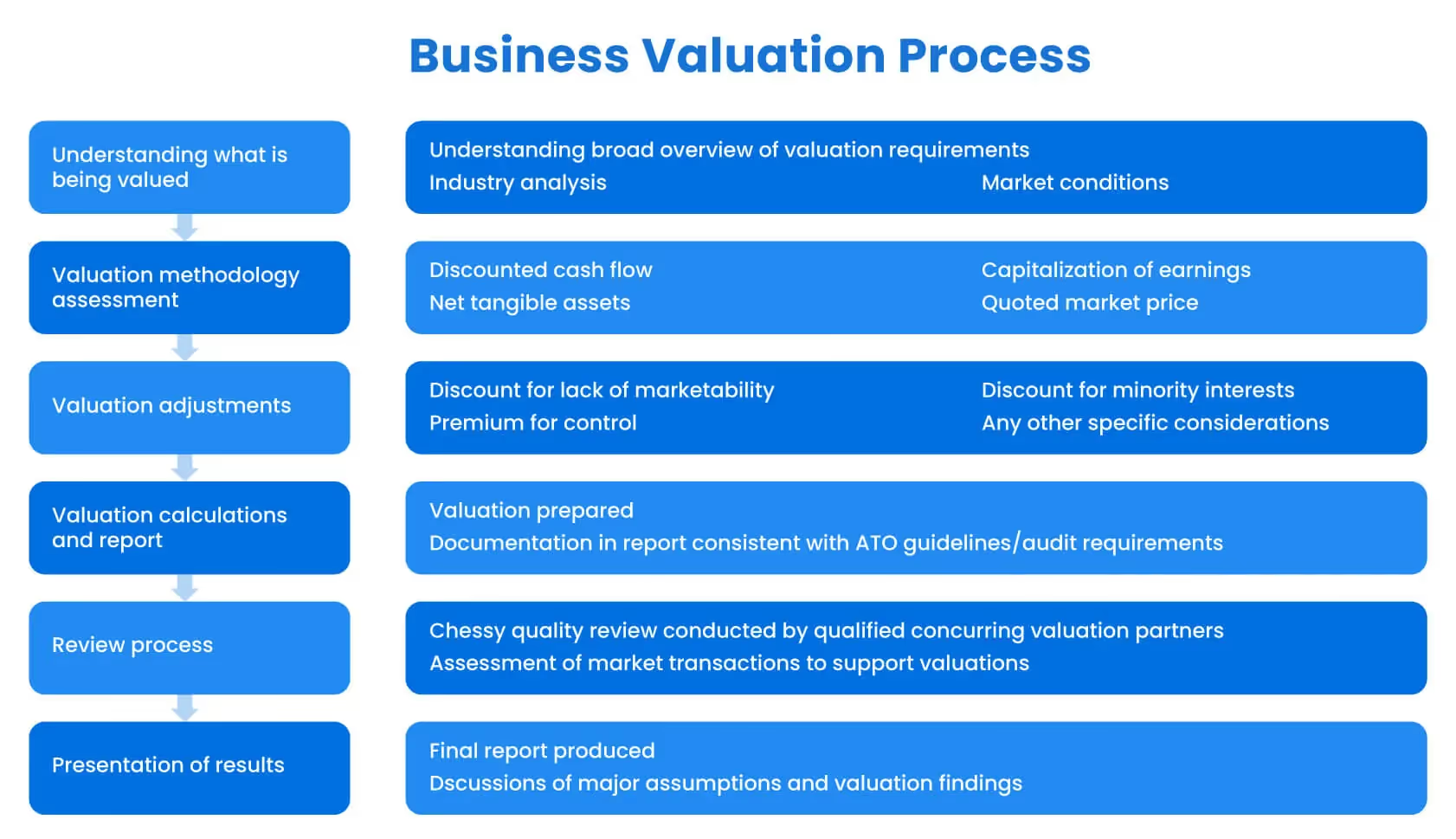

The Business Valuation Process

The process differs based on the business valuation methods being used.

Whatever method you use, the ultimate goal is to determine the company’s intrinsic value.

The appropriate approach often depends on the context, such as whether the company is public or private and who is conducting the valuation. Should a company be measured based on its assets, its future free cash flows, recent transactions for comparable companies, or the sum of its real options? In practice, most valuation professionals rely on a combination of methods to cross-check results and build a more reliable estimate.

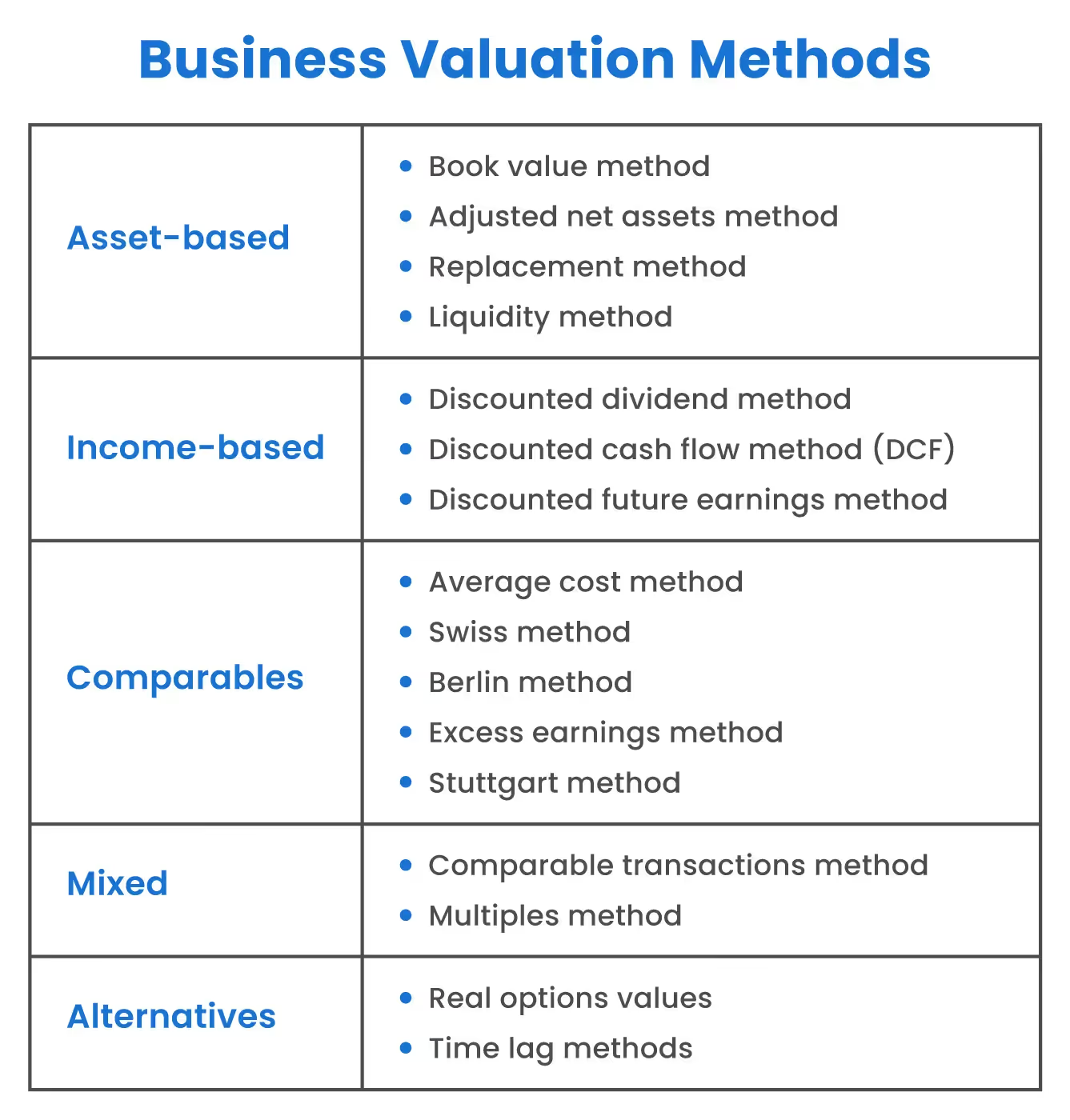

The table below summarizes common valuation methods.

Typically, business valuation professionals use at least two methods when valuing companies, the most common being the DCF method and comparable transactions. These methods are popular because they’re widely understood, and the underlying numbers are easier to obtain. In the case of real options valuation, for example, the numbers that underpin the value of the business are far more difficult to objectively ascertain.

1. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

Discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis uses the inflation-adjusted future cash flows to project a value for the business. The idea is simple: free cash flow is the ultimate driver of shareholder value.

The challenge lies in the execution. Forecasting free cash flows years into the future requires assumptions about growth rates, terminal value, and the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Even small changes in these inputs can produce wide swings in valuation, which is why DCF is both widely used and frequently criticized.

DCF = CF1 / (1+r)1 + CF2 / (1+r)2 + ....+ CFn / (1+r)n

Where, CF1 = The cash flow for year one, CF2 = The cash flow for year two, n = Number of years, r = Discount rate

For example, let's consider a company with a projected FCF of $1 million for the next 5 years. Assuming a discount rate of 10%, the company's future cash flows amount to approximately $3.79 million.

2. Capitalization of Earnings Method

The capitalization of earnings method is a neat, back-of-the-envelope method for calculating the value of a business, which is actually used in DCF Analysis to calculate the perpetual earnings (i.e., all those earnings that occur after the terminal year of the DCF Analysis being performed).

Sometimes called the Gordon Growth Model, this method requires that the business have a steady level of growth and cost of capital. The numerator, typically the free cash flow, is then divided by the difference between the discount rate and the growth rate, expressed as a fraction, to arrive at an approximate valuation.

Market Capitalization = CF1 / (r-g)

Where, CF1 = Cash flow in the terminal year, r = Discount rate , g = Growth rate

For example, consider a company with a projected FCF of $1 million in the terminal year, a discount rate of 10%, and a growth rate of 5%. Using the capitalization of earnings method, the company's value would be approximately $20 million.

3. EBITDA Multiple

The EBITDA multiplier is an excellent solution to the arbitrary nature of most valuation methods. Even Aswath Damodaran, the father of modern valuation, says that any business valuation should follow the law of parsimony: the simplest of two (or more) competing theories should hold sway in an argument.

On this basis, the EBITDA multiple - the multiplication of this year’s EBITDA figure by a multiplier agreeable to both the buyer and seller - is an elegant solution to the valuation dilemma.

Even those who consider this method too simplistic tend to use it as a guide for their valuations, which underscores its strength.

4. Revenue Multiple

This method can be used in those circumstances where EBITDA is either negative or isn’t available for some reason (usually because sales figures are the only ones available when researching firms to acquire through online search).

Again, while you might say it’s just a benchmark, others would argue (with some justification) that the business’s total sales is the most important benchmark of all.

5. Precedent Transactions

This method may incorporate the EBITA and revenue multipliers or any other multiple that the practitioner wishes to use. As its name suggests, here the valuation is derived from comparable transactions in the industry.

So, for example, if widget makers have been trading at multiples of somewhere between 5 and 6 times EBITDA (or net income, or whatever indicator is chosen), Widget Co. would establish its value by performing the same iterative process.

The challenge, however, is determining how truly comparable one company is to another, even within the same sector. For this reason, precedent transactions are often viewed less as a precise valuation tool and more as a barometer of current market sentiment.

6. Book Value/Liquidation Value

Liquidation value, often referenced by Warren Buffett, represents the net cash a business would generate if all liabilities were settled and its assets sold off today.

Strictly speaking, it’s not a full business valuation method, since it only captures part of the company’s worth.

However, to paraphrase Buffett, it allows you to see the ‘margin of error’ associated with a valuation.

Even if management falters or the company’s sales fall dramatically after the acquisition, investors know the company retains fallback value in its assets.

7. Real Option Analysis

Proponents of real options analysis view businesses as nothing more than a nexus of real options: the option to invest in opportunities, utilize spare capacity, hire additional salespeople, etc.

Valuation, in this sense, comes from quantifying the flexibility and strategic choices available to management.

This is most effective for firms with uncertain futures, usually those that aren’t yet cash-flow positive, such as startups and mineral exploration firms.

While it is one of the most complex methods on this list, it has strong academic backing and is taught by institutions like McKinsey and leading business schools.

8. Enterprise Value

Enterprise Value (EV) measures the total value of a company’s operations by accounting not only for equity but also for debt obligations and cash reserves. By including debt, we can provide a more accurate picture of a company’s value (especially in the context of mergers or acquisitions), as it represents the total cost to acquire the company’s operations.

EV = Market Capitalization + Total Debt - Cash and Cash Equivalents

For example, if a company has a market capitalization of $50 million, total debt of $20 million, and cash reserves of $5 million, its enterprise value would be $65 million ($50M + $20M - $5M).

9. Present Value of a Growing Perpetuity

The Present Value (PV) of a Growing Perpetuity is a valuation method that’s used to estimate the total value of cash flows that continue indefinitely and grow at a constant rate. It's often applied when a business is expected to generate recurring stable cash flows without a foreseeable end. We can calculate the present value of a growing perpetuity with:

PV = C / (r-g)

Where:

- C = Cash flow at the end of the first period

- r = Discount rate

- g = Growth rate

For example, if a company generates a cash flow of $1 million at the end of the first period, and the discount rate is 8% with a growth rate of 3%, the present value of its growing perpetuity would be $20 million.

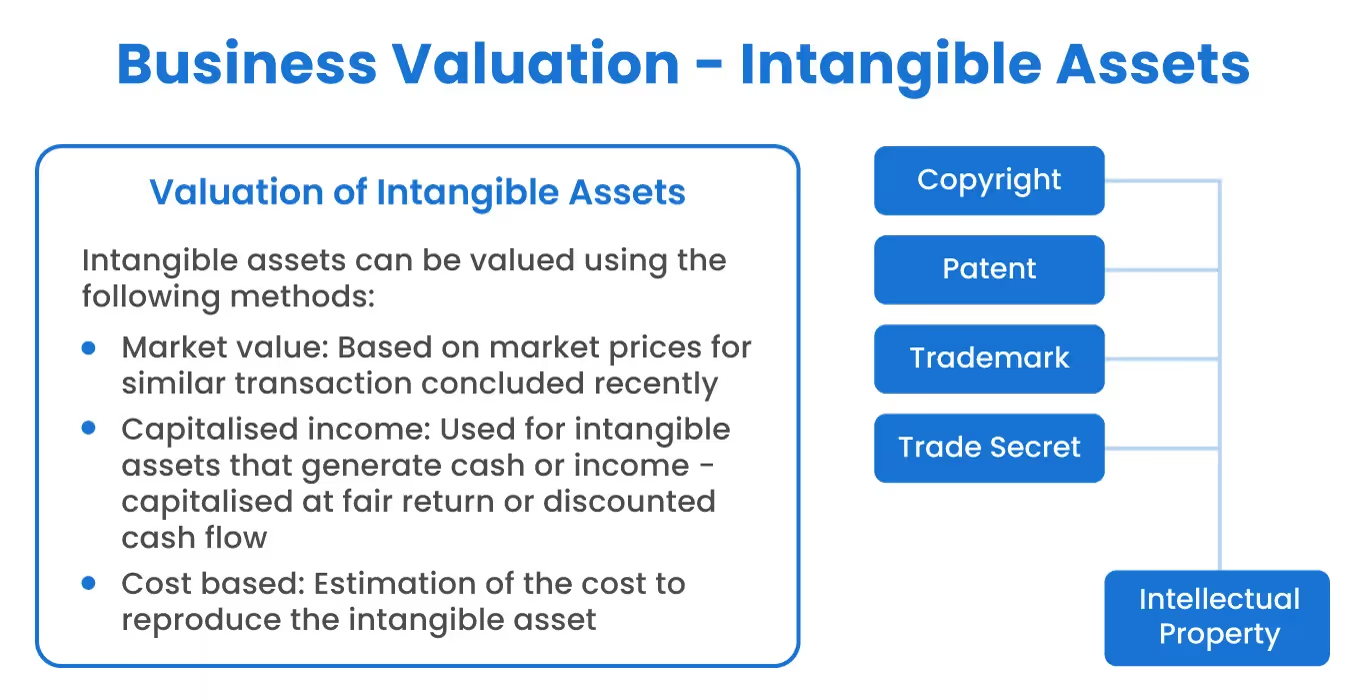

Valuing Intangible Assets

In today’s economy, intangible assets often drive more enterprise value than physical ones. In industries like technology, healthcare, and consumer goods, factors such as brand reputation, intellectual property, proprietary data, and customer relationships can often be worth many times more than tangible assets like factories and equipment. However, quantifying intangibles remains a major challenge.

Brand value

From driving pricing power to inspiring customer trust and loyalty, strong brands can have a material effect on a company’s performance. At a high level, two companies with the same business model selling the same product might trade at very different valuations based on name recognition alone.

Analysts typically benchmark brand value using methods such as the royalty relief approach (estimating what it would cost to license the brand) or by attributing a portion of the premium margins that the brand enables.

Proprietary technology and patents

Patents, algorithms, software code, technical know-how, and other intellectual property (IP) assets can be the single most important valuation drivers for certain companies, particularly in biotech and SaaS. The value of patents or IP portfolios can be estimated through modeling their future income streams (protected by the IP) or by identifying comparable licensing or acquisition transactions.

Analysts may also use real options analysis to capture optionality created by underlying technology platforms that have the potential to launch new products or expand to new markets in the future.

Data assets

Proprietary consumer or transaction data, web traffic, scientific datasets, maps, geospatial data, or other forms of digital information have become valuable monetizable assets in their own right. Valuing data typically involves estimating its incremental revenue potential (e.g., enabling targeted advertising or product innovation) or its ability to generate cost savings. Emerging approaches now apply alternative data analytics to assess a dataset’s uniqueness, scale, recency, and actionability, providing a more objective measure of its strategic value.

Customer relationships

Recurring revenues, renewal contracts, and other forms of long-term customer agreements or relationships can also be a critical driver of enterprise value. To measure these economic benefits, analysts use customer lifetime value (CLV) models, churn-adjusted revenue forecasts, and other relevant metrics.

For SaaS businesses, for instance, recurring revenues are particularly reliant on renewal rates, and metrics like net dollar retention are often the key determinant of whether a business can command a premium multiple.

Emerging approaches

Accounting standards are often ill-equipped to deal with intangible value, but newer approaches are filling the gap, such as:

- Machine learning models using alternative data (e.g., social media sentiment, web traffic, supply chain signals) to value brands or products. LinkedIn, Spotify, and Squarespace all trade at premium multiples, in part due to network effects and stickiness that social media sentiment analysis can corroborate.

- IP analytics platforms value patents by examining factors such as breadth, citation strength, and litigation history to benchmark against other players in an industry.

- Customer engagement metrics, such as Net Promoter Scores and app usage frequency, can be tied to future retention and cash flow stability.

- DealRoom’s M&A Platform integrates intangible valuation into deal workflows by linking data on customer relationships, IP, and synergy potential directly into valuation models. This helps buyers move beyond financial statements, quantifying the strategic value of intangible assets and tracking whether those assumptions are realized post-close.

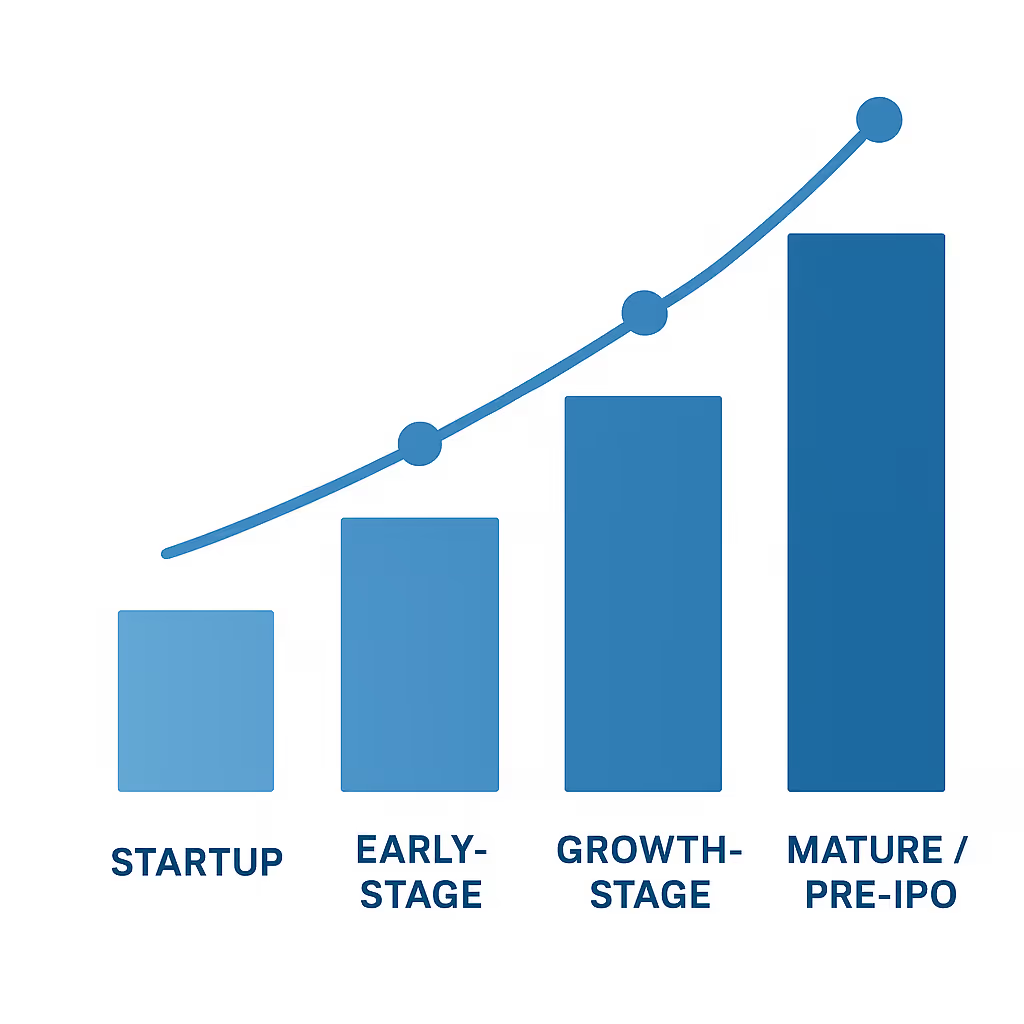

Valuation in Different Company Stages

Valuation approaches may be influenced by the stage a company has reached in its lifecycle. There’s no hard and fast rule for choosing a valuation method based on the stage of development, but it’s worth bearing in mind that data availability, cash flow predictability, and value drivers can change significantly as a company matures.

Startups and early-stage companies

Startups, such as companies that have recently emerged from incubators, often lack stable earnings. In some cases, they may be pre-revenue. In this situation, DCF analysis becomes unfeasible as future cash flows become highly sensitive to input assumptions and cannot be projected with confidence.

Multiples and comparables based on revenue multiples, or real options approaches, may be more suitable here. Revenue multiples provide a market-based benchmark when only top-line figures are available. Real options capture the flexibility and potential upside in early-stage investment decisions, such as product launches or geographic expansion.

Growth-stage companies

As growth-stage companies start to scale and generate more predictable revenues, the toolbox of valuation methods widens. Multiples remain common in these valuations, but investors often augment them with forward-looking methods such as DCF, particularly when recurring revenues or signed contracts make future cash flows easier to predict.

Growth assumptions become more influential on valuation at this stage, and scenario analysis is often used to assess whether a valuation remains intact under different growth assumptions or market conditions.

Mature and pre-IPO enterprises

Established companies with years of stable earnings history are suitable candidates for DCF analysis as well as synergy-based valuation. DCF analysis can provide a more accurate sense of the business's intrinsic value when historical data allows for more precise projections.

Synergy-based valuation also becomes applicable in M&A situations, as buyers need to quantify expected cost savings, operational efficiencies, or revenue synergies to justify an acquisition premium. Analysts often triangulate between DCF, comparable company multiples, and precedent transactions to estimate a valuation range that suits both private and public investors when assessing pre-IPO companies.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and common valuation methods for companies in various stages of growth.

Industry Differences in Business Valuation

Industry-specific factors can also influence the effectiveness of various valuation methods. A methodology that suits a SaaS business might be unsuitable for a manufacturing firm or a biotech company. The value drivers, accounting standards, and risk factors vary significantly by industry, which influences the prominence of different valuation approaches.

Software companies, for instance, often pivot on recurring revenues and customer lifetime value, while biotech companies may be valued on the probability of success in clinical trials and future licensing milestones. Asset-heavy businesses, like real estate or manufacturing, place greater emphasis on book value and replacement cost methods.

Recognizing these industry-specific patterns can prevent apples-to-oranges comparisons and give a better sense of real-world investor valuations. Let’s take a look at a few examples in different industries.

SaaS Startup (Technology)

A SaaS business is generating $10M in ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) with 80% gross margins. It’s valued primarily on a revenue multiple, as this best reflects market expectations. Investors compare it to other SaaS companies in the market that trade between 8-10x ARR, adjusting for the company’s churn rate and growth rate.

DCF analysis is not ideal for SaaS companies due to the unreliability of long-term projections; however, ARR multiples can quickly capture the company’s market potential and scalability.

Biotech Firm (Pharma)

A biotech company is currently in Phase III trials for a new cancer drug, with no current revenue but promising trial data. Analysts would use a probability-adjusted DCF model based on future milestones like FDA approval and market launch.

They would assign probabilities to each stage (e.g., 30% chance of passing Phase II, 60% chance of Phase III, etc.) and discount the expected royalty revenue stream from future sales.

Valuation here is a blend of scientific data and statistical probabilities of commercial success.

Manufacturing Company (Industrials)

An auto parts manufacturing company owns three manufacturing plants, has steady long-term customer contracts, and generates $25M in EBITDA per year. The company is valued using an EBITDA multiple (e.g., industry multiple of 6x = $150M enterprise value) as well as an asset-based analysis for downside protection to ensure the plants and equipment are valued appropriately.

The focus is on tangible assets and predictable, recurring cash flow.

The table below highlights some industry-specific valuation approaches for key industries.

How to Pick the Right Valuation Method

As noted earlier, most business valuation professionals rely on at least two methods, and the final output is only as reliable as the quality of the input.

After conducting a preliminary analysis, the valuer selects the approach most appropriate for the company and its industry.

The single biggest determinant is often information availability. For example, comparable transactions cannot be used if there are no sufficiently similar deals to reference.

Consider, for example, the challenge of valuing intangible assets.

Even transactions in the same industry from several years ago may no longer reflect current market realities, making direct comparisons unreliable.

Similarly, even the most widely used methods like DCF require users to forecast free cash flows years into the future. Only in exceptional cases, such as a company with a remarkably small client base and pre-agreed long-term contracts, can forecasts be made with a high degree of confidence.

But information availability is just one factor in selecting the right valuation method. Other key considerations include:

"The thing that comes to mind for common blind spots is the projections - the growth of the revenue, and probably secondary, synergies. You really have to drive some reality and pressure on that. Your analysis definitively needs a downside case so people aren't surprised if it doesn't pan out."

Speaker: Keith Crawford, Global Head of Corporate Development, State Street Corporation

Shared at The Buyer-Led M&A™ Summit (watch the entire summit for free here)

Type of the company

For light-asset businesses such as service firms, it makes little sense to use the net-asset valuation method. Similarly, if most of a company’s value is in its branding or IP, the discounted cash flow method may not capture its true worth.

Size of the company

Larger companies typically support a wider range of valuation methods due to richer data availability. Small companies, with less information, may only be suited to a handful of valuation methods. It’s also important to note that larger companies often command higher valuation multiples.

Economic environment

The broader market climate plays a critical role. In strong economic conditions, it’s important to be somewhat conservative when valuing, with the understanding that all business cycles come to an end.

End users

The intended audience also shapes the method. Some buyers may focus primarily on fixed asset value, such as technology, real estate, or even trucking fleets. Others prioritize cash-flow potential, as is common in SaaS and subscription-based businesses.

Business Valuation in Today’s Environment

Business valuations vary based on the broader economic and investment climate. Today, several factors are impacting both company valuations and the most effective methods for evaluating them.

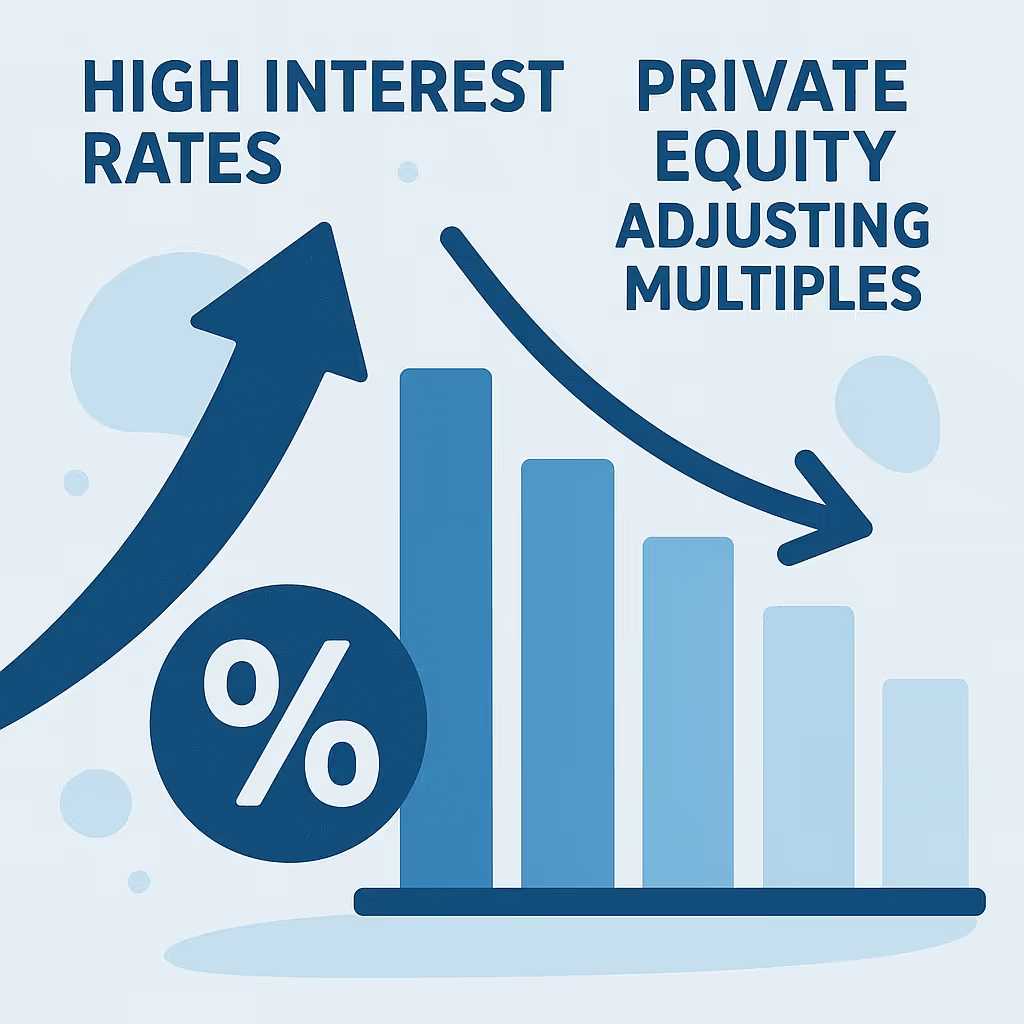

Impact of high interest rates on DCF

Discounted cash flow has always been an inexact science due to assumptions about future cash flows. However, when interest rates rise, so does the discount rate, which has a material impact on the present value of future cash flows and can result in lower valuations, even for fundamentally strong businesses. Deal teams are revisiting growth assumptions, tweaking the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), and running higher/lower scenarios to account for interest rate uncertainty.

Private equity adjusting multiples

Private equity is also adjusting the way it values potential targets. For years, PE firms have leaned on EBITDA and revenue multiples to assess value. However, in an environment of more expensive capital, buyers are tightening the multiples they are willing to pay, and not paying up for top-line growth alone.

PE investors are instead rewarding companies that can show high levels of operational efficiency, predictable cash flow, and significant cost synergies that can be captured post-deal.

The rising importance of intangibles

Gone are the days when a company’s value could be found primarily through tangible assets. In many industries today, intangibles such as intellectual property, brand recognition, proprietary data, and customer relationships can be the primary value drivers of a business.

This is especially the case in SaaS, technology, and healthcare industries, where intangibles can comprise the majority of enterprise value. Valuation approaches that overlook these assets can easily miss the mark. To address this, analysts are now focusing on qualitative factors and integrating alternative data sources to help value intangibles.

From valuation to value creation

Strategic and financial buyers assess businesses based on current performance and potential future growth at one and three years post-close. From revenue growth to cost savings and monetizing intellectual property, expected synergies can create value that justifies a buyer paying a premium, even in more risk-averse markets.

With DealRoom’s M&A Platform, buyers can easily map their valuation to their post-closing integration planning and validate that expected synergies are no longer just assumptions, but tracked and captured throughout the deal process.

Common Valuation Pitfalls

Valuation methods can produce faulty results without realistic and properly supported assumptions. Awareness and avoidance of common mistakes are crucial for analysts and deal teams to ensure sound investment decisions.

Over-optimistic growth forecasts

Charting double-digit growth rates into perpetuity can seem appealing in a valuation model, but in reality, very few businesses can maintain such expansion. For instance, a SaaS startup may project 40% year-over-year growth over the next ten years without considering competitive market dynamics or saturation.

Seasoned professionals apply sensitivity analysis and stress-test their forecasts with conservative, base-case, and downside scenarios to maintain realistic valuations.

Ignoring working capital needs

DCF models that highlight free cash flows may sometimes disregard the importance of working capital. A manufacturing firm may project $20M in annual cash flow but could actually require $5M per year to be reinvested in working capital to maintain operations, leaving only $15M of true free cash flow.

To address this, analysts pay close attention to net working capital adjustments when modeling operating cash flows.

Misapplying multiples

Benchmarking against industry multiples is a common practice, but applying them blindly can be misleading. For example, using a 10x EBITDA multiple from a high-growth technology firm to value a slow-growing industrial company can result in an inflated valuation and a skewed view of the market.

Experienced dealmakers choose comparable companies judiciously and make adjustments for size, growth, and profit margins before applying multiples.

Failing to account for cyclicality

Industries that are sensitive to economic cycles, commodity prices, or housing markets can appear more robust than they are if valued at the top of a cycle. For example, a construction company may seem to have a much higher valuation during a building boom than what would be realistic once the market normalizes.

Professionals either normalize earnings over a full economic cycle or use mid-cycle metrics to value such businesses.

Overlooking intangibles

The value of tangible assets can often be quantified easily, but failing to consider intangibles such as brand value, intellectual property, or customer relationships can lead to an undervaluation of a company. For example, a consumer goods brand might trade at a premium to its book value because of a strong, loyal customer base.

Valuation experts are increasingly accounting for intangibles or looking to alternative data sources to understand these less visible value drivers.

How to Carry Out a Successful Valuation of a Company

Valuation professionals can take several steps to ensure that, regardless of the method used, their analysis produces a result that closely approximates intrinsic value.

Successful valuation factors are:

Objective

A valuation which is heavily influenced by an opinion can be regarded as just that - an opinion.

Holistic

The valuation should consider as much information as possible - not just a company’s assets or its cash flows, but also its environment and other internal and external factors.

Simplistic

Holistic does not mean detail for the sake of detail. Valuing Amazon doesn’t require making projections about the future prices of cardboard packaging.

Justifiable

Anyone reading the valuation should be able to arrive at the same conclusion as the individual conducting the valuation based on the information provided.

Business valuation providers

Business valuation is the bread and butter of investment banks and M&A intermediaries.

Even if a company has the wherewithal to conduct its own business valuation, hiring a third-party specialist is often worthwhile.

Depending on the valuation method(s) used, professional business valuation providers can adjust inputs over time to show how a company’s valuation evolves. Accredited business valuation specialists can also ensure accuracy and reliability by adhering to industry standards and bringing objective insights that help companies make informed decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which business valuation method is the most accurate?

There is no single "most accurate" method. The best approach depends on the company's industry, size, stage of development, and the purpose of the valuation. Professionals often use a combination of methods (like DCF and Comparable Transactions) to triangulate a fair value. A method is only as accurate as the quality and reliability of its inputs.

Is the Book Value the same as what my company is worth?

Almost never. Book Value is an accounting value based on the historical cost of an asset minus its accumulated depreciation. It often ignores critical value drivers like intangible assets (brand, IP, customer relationships), future earnings potential, and market conditions. A company's true market value can be significantly higher or lower than its Book Value.

How do you choose the right discount rate (WACC) for a DCF analysis?

The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is a complex but critical input. It represents the average rate of return required by all of the company's investors (debt and equity holders).

It’s typically calculated by weighing the cost of equity (often estimated using methods such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model, or CAPM) and the cost of debt, based on their proportional use in the company's capital structure. For private companies, this often involves benchmarking against similar public companies.

Why do valuation professionals use multiple methods?

Valuation professionals rely on multiple methods to establish a range of values rather than a single, potentially misleading figure. By cross-validating results, they can confirm or challenge the outcomes of individual approaches while incorporating different perspectives such as asset value, income potential, and market comparables. This broader view provides deeper insight into a company’s worth and increases confidence in the final estimate, especially when the methods align on a similar value.

When should I use a DCF analysis versus a Multiple-based approach (like EBITDA multiple)?

You should use a DCF analysis when you have reliable and predictable cash flows, as well as a clear view of future growth. This method is ideal for companies with stable business models and is considered a fundamental, intrinsic valuation technique.

On the other hand, a multiple-based approach, such as an EBITDA multiple, is better suited for quicker, market-based valuations, comparing companies within an industry, or when cash flow projections are highly uncertain. Multiples are particularly useful for gauging what the market is currently paying for similar businesses.

What is the difference between Equity Value and Enterprise Value (EV)?

Equity Value, often referred to as Market Capitalization, represents the value of all a company’s outstanding shares and reflects the portion attributable to shareholders. Enterprise Value (EV), however, captures the total value of a company’s operations, including both debt and equity holders. It’s calculated as Equity Value plus Debt minus Cash. EV provides a clearer picture in acquisition contexts, as it represents the theoretical takeover price of the business.

Final Thoughts

The constant fluctuation of stock prices underscores a simple truth: there will never be a single, universally accepted valuation for any company.

Blue chip Investment banks, keen to let everybody know that they’re hiring the best quantitative analysts in the world, can also vary widely on price. For instance, Chime, the digital banking platform, went public at a valuation 62% below its peak private-market value, demonstrating how even well-known, financially growing firms can be priced significantly lower than private valuations suggest.

Every method has its limitations. Analysts frequently adjust inputs until the results “feel” more reasonable, underscoring the subjectivity of the process. The best practice is to apply multiple methods (examining revenues, EBITDA, free cash flows, assets, and real options) to build a well-rounded perspective of a company’s worth.

The DealRoom M&A Platform optimizes the M&A process to increase efficiency and accelerate synergy realization. By organizing and managing the pipeline, streamlining due diligence, and linking valuation assumptions directly to integration planning, DealRoom empowers deal teams to value businesses more effectively. It also helps them track and capture the expected synergies after the deal closes.

The DealRoom M&A Platform optimizes the M&A process to increase efficiency and accelerate synergy realization.Whether you need an advanced M&A pipeline tool to enable pipeline management or an end-to-end M&A platform to manage your complete lifecycle, DealRoom has the solution for you.

Get your M&A process in order. Use DealRoom as a single source of truth and align your team.

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)