“Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”

Warren Buffett

Quotes from the Sage of Omaha are more regularly associated with investing in public companies, but in this case, the shoe fits for acquisitions.

Before discussing how to calculate the acquisition price of a company, it’s important to underline that the price is just one component of the acquisition.

Even when a company is acquired for a knockdown price - or at least, what is perceived to be a knockdown price - it could transpire that the company paid too much.

That’s because the price you pay is only one component of the value you gain.

As most ‘how to’ guides on M&A are keen to emphasize, a significant percentage of the value in a deal is unlocked in the integration phase (hence, the need for a change manager).

All that said, you give your deal a much better chance of generating value if the acquisition price is right.

We at DealRoom work with many companies organizing their M&A process and below, we have put together some strategies you should employ when calculating the acquisition price of a company.

These rules are general enough to hold true for a small company making its first foray into mergers and acquisitions, or a much larger firm with a long track record of closing deals.

What is an acquisition price?

The acquisition price of a company is the total consideration paid for the company on an agreed date.

It’s important to note, however, that as a good proportion (or indeed all) of the consideration paid could be the equity of the buyer, the acquisition price could depend on how the market reacts to the transaction.

If the market reacts well to news of the deal, the value for shareholders would rise thanks to an increase in the stock price, with the opposite happening if the market reacted badly.

Furthermore, for the sake of accounting, the acquisition is considered an acquisition of an asset.

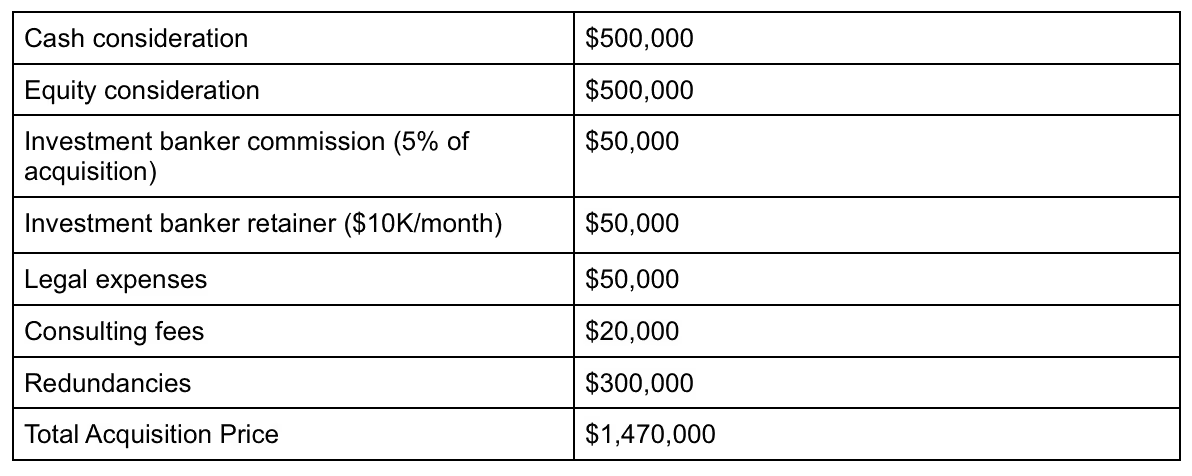

As such, the acquisition price which will appear on the company’s financial statements is not just the price agreed between the two companies, but also the cost of making the transaction a reality, including legal fees, outside consultants’ fees, brokerage fees, and more.

How to determine acquisition price

Let’s suppose that your company acquires a company for $1 million for an even breakdown of cash and stock.

Let’s also assume that there were some other costs involved in making the deal a reality (including the integration costs).

There is some flexibility on these costs, as companies can contract investment bankers and ultimately not make any acquisitions, in which case, these would be pure operational costs.

If the acquisition closes, the expenses can be capitalized, however.

The acquisition price might look something like the following:

With the costs adding up so quickly, it’s easy to see why it’s so important to make sure, i) that there’s a strong motive for the acquisition in the first place, and ii) that the consideration being paid for the acquisition is fair relative to the target company’s intrinsic value.

How to determine the price properly

Understand that there has to be a good motive for the deal.

If you ask yourself ‘why are we making this acquisition?’, and you don’t have a clear response, you’re already reducing the chances that you’ll be able to calculate an acquisition price for the company.

Because if there’s no ‘why,’ there’s probably not a good acquisition price.

This leads into another issue: the calculation of the right price depends on how it fits with your business.

To use a simple example, an acquisition which gives you market share in a territory where your company currently has no presence will be worth more to you than companies that already do business in that territory.

We’re talking here about the value of synergies. But bear in mind…

Get a second opinion

One of the most common mistakes of buyers is to let the grand vision cloud their perspective. A business should only be bought when the numbers make sense.

When you believe that they do, you should ask a second opinion. And this is important - the second opinion should be from a trusted third party, not the investment banker who stands to gain from the transaction.

As we mentioned before, you don’t always need an investment banker in any case.

A few expert opinions are better than one. This gives a range of different perspectives - say, on the technical, marketing, finance and legal aspects of the transaction.

When calculating the value of the deal, don’t just look at your own expertise, draft in intelligence from other areas. Gain any edge when calculating the acquisition price that you possibly can.

"At one point, I had a banker call me at dinner and say we have a problem - we just lost $25 million in EBITDA. I said why? He said the asset manager repriced the fees. $25 million of EBITDA at maybe 8 to 12 times - that kills a deal."

Speaker: Keith Crawford, Global Head of Corporate Development, State Street Corporation

Shared at The Buyer-Led M&A™ Summit (watch the entire summit for free here)

The value of synergies when calculating the acquisition price

Spend some time reading the financial accounts of public companies and something will quickly become apparent: The notes sections that accompany financial statements are a graveyard for targets for which the buyer vastly overrated the synergies and ended up writing down the value of the acquisitions.

This happens to even the most experienced companies.

Microsoft is a culprit that springs to mind. In the past decade, it has written down investments in Nokia ($7.5 billion) and aQuantive ($6.2 billion), and may yet end up doing so with LinkedIn.

SMEs, however, don’t have the same cash reserves that Microsoft can fall back on, so write downs tend to be more damaging.

Thus, a good way to think about synergies when calculating the price of an acquisition is not to think about them at all.

That is - there should be synergies behind the motive for the deal, but not in arriving at the calculation price. Synergies do exist. But in the majority of cases, trying to calculate them will only lead to you overpaying.

Paradoxically, the thing which you believe will generate value can end up destroying it instead.

Use more than one valuation tool

As mentioned in a previous post, there are a number of different valuation methods, so there’s no sense in limiting yourself to just one.

At a minimum, acquirers should look to use two methods for valuation - with one industry multiple (EBITDA or revenue, usually) being used to complement another, usually the discounted cash flow or book value.

The industry EBITDA multiplier is relatively straightforward, but remember which end of the industry you’re operating in: Databases like CapitalIQ will provide useful figures on multipliers but you shouldn’t compare NASDAQ companies with SMEs.

For the record, a database like Platt’s is usually a better barometer for multipliers for smaller companies.

Aligned to this, it can be useful to gain a second opinion on value as well. We’re not suggesting you confuse the issue by having too many valuations - merely that you take a few valuations and think of them as a range for the price.

Clearly, the closer you can get to the bottom of that range in your transaction, the better a chance the deal has of generating value.

Key Takeaways

The justified emphasis on change management and integration over the past decade may have led us to underestimate the importance of price to the success of an acquisition.

Price is fundamental. Applying science and rigor to this stage of the M&A process is just as important as doing so later on in the transaction.

Do everything to ensure that you’re achieving a good transaction price now, so that you’re not paying the price further down the line.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)