Private Equity Fund Structure: Partners, Fees & Pay, How it Works

Private equity funds constitute a significant proportion of DealRoom’s clients, putting us in close contact with these companies, their leaders, strategies, and transactions.

DealRoom supports PE deal success across the entire lifecycle, allowing us to share some of the insights we’ve gleaned from these private equity clients and our interactions with them over the years.

What is a Private Equity Fund?

A private equity fund, is a fund managed by a private equity firm, that pools investors’ money to make equity investments in private companies according to a particular strategy. The term ‘private’ is important here, as it distinguishes these companies from those publicly listed on stock indices.

In order to obtain the investors’ (‘limited partners’ or ‘LPs’) funds, the managers of the private equity companies (‘general partners’ or ‘GPs’) outline the goals of the fund, its strategy, and how long the investors need to wait to see a return on their investment.

Below is an example PE fund structure based on the Delaware limited partnership (LP).

.avif)

Understanding Private Equity Funds

Private equity offers a universe of opportunities that simply aren’t available to traditional stock market investors.

In the United States, at any one time, there are around 5,000-6,000 listed companies. Below is a breakdown of PE fundraising activity in the previous years.

.avif)

Compare this to the country’s estimated total of 6 million private companies. This is the group of companies - for the most part - where private equity funds focus their investment efforts.

.avif)

We say, ‘for the most part because sometimes private equity funds can acquire publicly listed companies and take them private (i.e. delist them). Some companies, one example is Burger King, have been listed and delisted several times over the past decade, as various private equity investors have sought to make financial and operational changes to the company with the intention of generating value for their investors.

To bring investors on board, the first thing that private equity partners (GPs) do is to create an investment thesis. This thesis outlines why the company’s chosen investment strategy will generate value. Below is a breakdown of the most common PE fund investors by type.

.avif)

The investment thesis is typically outlined in a slick document put together by the private equity company, which typically outlines several details to entice the investor. These include:

Partner profiles

Outlining the experiences and successes of the private equity company’s managing partners.

Other funds managed by the company

Many funds will follow the same strategy as a previous fund now closed to investment (hence, they gain names such as ‘International Energy Fund I’ and ‘International Energy Fund II’). If these funds have been successful, the document will outline their performance from their launch to date.

Companies in the pipeline

The document will usually show companies that the private equity company has opened discussions with, as well as the status of how those discussions are going.

Goals of fund

Most of these are financial goals, but the document will outline how these goals will be achieved (e.g. a combination of operational performance improvement, financial engineering, and reduction of employees). This will also include details on how long the fund intends to be operational (with most funds having a pre-defined life period, after which they are liquidated).

Management fees

This will be discussed in more detail below but is a crucial component of the offering memorandum sent to investors to whom the private equity fund is being marketed.

Minimum participation

The private equity managers set a threshold level on the investment in a fund: Unless a threshold percentage of the target investment in the fund is met (let’s say 30% of a target $100M), the fund may be discarded, and the funds provided by other investors can be returned.

Management and Responsibilities

The management and responsibility of the company acquired by the private equity fund are of crucial importance. It’s one thing to invest in a company - it’s quite another to provide the expertise required to improve that company’s performance and generate the returns promised in the investment memorandum.

This is where the difference between the management company and the general partner (GP) arises.

The management company (or ‘fund manager’) is responsible for putting in place the team required to implement the private equity fund’s strategy in the company or companies acquired. The management company can be affiliated with the GP, but this doesn’t necessarily have to be the case.

In essence, the management company is a more specialized version of the private equity company, hiring on-the-ground expertise, and enabling the private equity company to scale up.

The General Partner (GP) is hired by the management company to manage the company’s operations and execute the strategy. The GP will have the required industry experience, enabling it to identify opportunities, invest in value-generating opportunities, ensure operational improvement at the company or companies, and employ the appropriate individuals to implement all of the above.

Fees and Compensation Payout Structure

Private equity fees largely depend on the previous performance of the General Partner. A team that has previously generated above-market returns on its investments will tend to charge accordingly.

The fee structure is divided into management fees and performance fees, each of which is explained in more detail below.

- Management fees: These are the fees - usually ranging between 0.5% and 3.0%, depending on the size of the private equity fund - that the GP charges for the management of the funds. Essentially, these fees are used to cover the operational expenses of the private equity firm.

- Performance fees: These depend largely on how the investment performs. The exact nature of the performance fees will be outlined in the initial investment memorandum. A typical fee structure would involve the first 5% of profit being returned fully to investors and anything in excess being divided between investors and the GP.

Private Equity Fund Strategies

The sheer scale of the opportunities open to private equity funds has inevitably led to a range of strategies to capitalize on them. A previous DealRoom article touches on just a handful of the strategies PE follows.

A further breakdown of PE fund strategies follows:

Venture Capital

Venture Capital is a form of private equity that focuses on early-stage companies that tend to offer high risk and high return. Learn more about the differences in our comparison of PE vs VC.

Growth capital

Whereby a slightly more mature company has identified growth opportunities and requires funds to exploit them (e.g. through acquisitions or access to new markets).

Real estate

Whereby the private equity company capitalizes on a larger market trend in real estate. A recent example would be the demand for warehouse space created by the growing e-commerce market.

Mezzanine financing

A form of financing outlined in some detail in our recent guide to mezzanine financing.

Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

In LBOs, the private equity company uses the investors’ funds in combination with a much larger proportion of debt to acquire companies and subsequently uses the company’s income to pay off the interest.

Funds of Funds (FoF)

A contrived strategy whereby the private equity fund invests in the investments of other investment funds (hence the name, fund of funds).

Private debt

Although running contrary to the idea of private equity, private debt is an increasingly popular private equity strategy. Essentially, the private equity company provides debt at a higher rate of interest to companies with the ability to repay the interest.

Distressed equity

A situation whereby the private equity company identifies companies that can generate cash, but have found themselves in a distressed financial situation owing to mismanagement or a volatile economic environment.

Why do Companies Choose PE Investments?

Increasingly, companies turn to private equity (PE) investments because of few alternatives. As traditional lenders (i.e. banks) become more regulated and faced stricter balance sheet controls, companies in the shadow banking industry (i.e. companies outside of regulated financial companies) have come to the fore.

Witness the incredible growth of dry powder over the past decade.

.avif)

Outside of the growth of dry powder, there are other reasons why private companies are turning more and more to private equity financing:

- Smart capital: Private equity GPs can provide a level of industry expertise beyond the realm of banks that can benefit private company owners.

- Flexibility: As the strategies above hint, private equity funds can offer a range of financing options, well beyond traditional financial institutions.

- Commitment: The infusion of PE cash represents a long-term commitment to the business that can generate considerable value for the company owner.

- Connections: Private equity funds often make portfolio investments, where an investment in one company will be complementary to others in the portfolio, enabling the portfolio companies to benefit from immediate synergies.

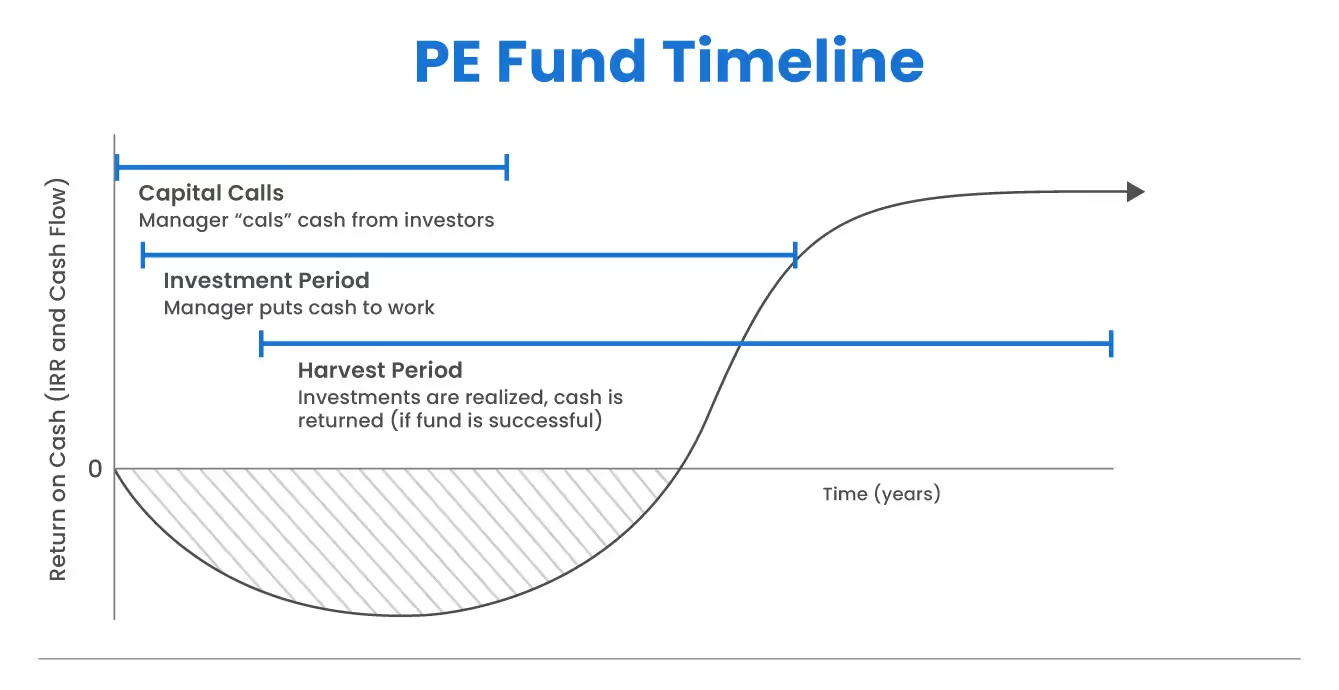

Private Equity Fund Lifecycle

The private equity life cycle depends to a great extent on the liquidity of the companies or assets acquired by the private equity fund.

For example, in a private equity fund focused on real estate, the lifecycle of the fund (i.e. from raising investor funds to liquidation) could be less than 5 years. In less liquid situations (e.g. manufacturing companies or specialist food and drink companies), the lifecycle could by anything up to 10 years.

Essentially, there are four broadly defined steps in the private equity fund lifecycle:

1. The capital raise

Even funds managed by high-profile private equity companies (think Blackstone, BlackRock, KKR, and others) can fail to get off the ground. The capital raise - the period in which investors’ funds are sought - can take up to two years. The pitch needs to be compelling. The team needs to be right. And even then, the threshold investment level may not be met.

2. Deal sourcing

Usually, before the fund has even started, the GP will have loosely identified a few companies or assets to acquire. Showing investors that these companies can be acquired at a reasonable multiple of EBITDA or income is crucial. A private equity fund will also typically include a time period in which it either has to acquire a company or return investors’ funds.

3. Post-acquisition operational improvement

Once a company has been acquired, it’s down the GP to grow its income. In the broadest terms, this means two things: i) growing top-line revenue, and ii) reducing operating expenses. Often, there will be some form of external leverage that accommodates both.

4. Liquidation

This occurs through a trade sale (i.e. a sale to a company in the same space or another private equity firm), or an IPO. The initial terms will define when this happens but it’s usually after five years and certain criteria are met (i.e. revenue or income growth). Private equity companies usually talk in terms of multiples of revenue, EBITA or income. At the liquidation stage, they’ll seek to achieve a certain multiple, which should be well above what the company or asset was acquired for in the first instance.

How DealRoom Can Help

Clearly, private equity is complex. The introduction of new strategies only adds to the complexity.

DealRoom has a long history working with top private equity firms, allowing us to witness a marked evolution in private equity, where outstanding returns demand even more sophisticated technology.

Private Equity firms trust DealRoom to boost their efficiency whether it's to raise funds, buy, restructure, or exit. (and repeat). Talk to us today about how our solutions can facilitate your private equity transaction, whatever the strategy.

Get your M&A process in order. Use DealRoom as a single source of truth and align your team.

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)