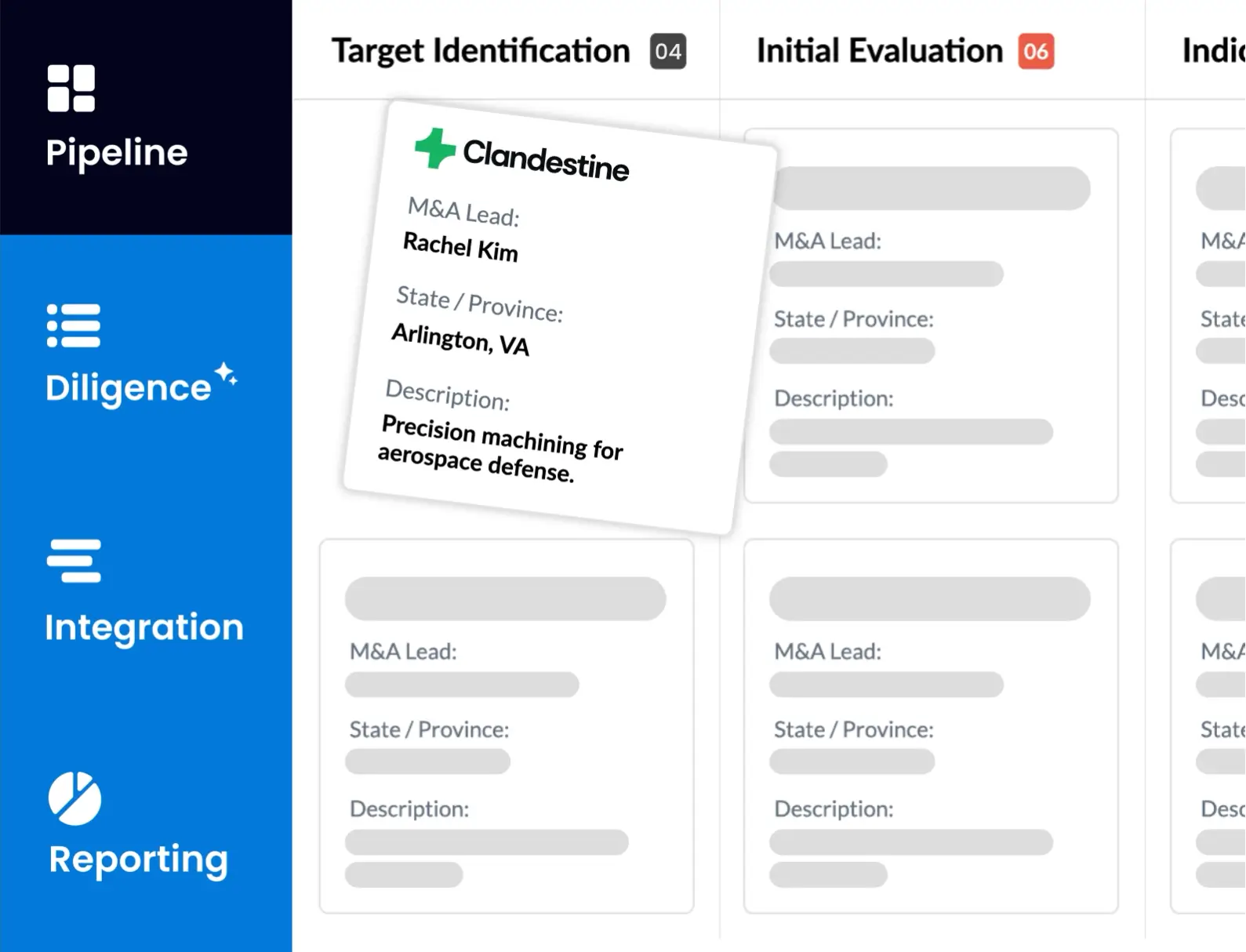

Few firms reach the very top without conducting at least a few mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions.

The fact that the most successful firms in the world employ teams of professionals whose sole role is to identify attractive potential acquisitions speaks volumes.

Implemented well, an active mergers and acquisitions strategy can be a highly fruitful process for any company.

At DealRoom, we work with dozens of companies to help organize their M&A processes, and below, we outline 15 of the biggest benefits of such a strategy.

What is a Benefit in Mergers and Acquisitions?

Benefits in mergers and acquisitions typically fall into three distinct categories:

- Strategic benefits, such as access to new markets, customers, or technology that cannot be easily or quickly built from scratch.

- Financial benefits, such as topline growth, cost reduction, or balance sheet improvement. Economies of scale and tax savings often fall under this category.

- Operational benefits, such as efficiency gains, talent, or system/process consolidation.

The reality is that not all deals will deliver these benefits. Valuations may not pencil out. Culture can clash, and integration can be more challenging than expected. Synergies can take years to materialize (if at all). And sometimes, the market changes can make the rationale of the acquisition redundant.

That’s why it’s helpful to think of synergies as possible opportunities rather than a certainty. Whether synergies are realized depends on how well the deal is structured, the timing of the deal, and, most importantly, how effectively post-merger integration is executed.

15 Benefits and Advantages of Mergers and Acquisitions

- Economies of Scale

- Economies of Scope

- Synergies in Mergers and Acquisitions

- Benefit in Opportunistic Value Generation

- Increased Market Share

- Higher Levels of Competition

- Access to Talent

- Diversification of Risk

- Faster Strategy Implementation

- Tax Benefits

- Financial Engineering and Capital Structure Optimization

- Value Chain Integration (Vertical Synergies)

- Brand and Reputation Benefits

- Cross-Selling and Up-Selling Across Lines

- Regulatory or Government Incentives in Certain Geographies

1. Economies of Scale

Underpinning all M&A activity is the promise of economies of scale. The concept is straightforward: larger size leads to improved efficiency, which in turn translates into increased competitiveness. Larger companies have easier access to more capital, as lenders and investors typically see them as a lower risk. For example, the fixed costs of technology infrastructure, distribution networks, or compliance teams can be shared across a larger revenue base.

The resulting operating costs to conduct business are also lower on a per-unit basis, as higher production or purchasing volumes make it easier to negotiate discounts with suppliers. Increased scale also often results in greater bargaining power with distributors, retailers, and talent markets.

The flip side of the economies of scale argument is that the actual benefit only goes so far, especially if the larger size does not serve a purpose. Growth for growth’s sake is often referred to as “empire building” and can lead to over-inflated structures, delayed decisions, and capital inefficiency.

The real benefit of size is when it is related to a particular strategy, such as increasing margins, giving more clout when bargaining, or competing more effectively in industries where efficiency is a differentiating factor.

2. Economies of Scope

Mergers and acquisitions bring economies of scope that aren’t always possible through organic growth. In contrast to economies of scale, where the average cost of doing business decreases as a firm produces more, economies of scope enable firms to more profitably serve additional markets and segments. Meta’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp are textbook examples.

Facebook already provided both photo sharing and messaging, but these M&A transactions allowed it to reach completely new user communities and value drivers that were not being as rapidly unlocked organically within its main product. This, in turn, enabled it to extract even more time and data from users, while simultaneously monetizing through the same advertising platform and infrastructure on a much larger scale.

The theory is that a business can establish an attractive platform, user base, or operational infrastructure, allowing it to expand into additional products or services at relatively low incremental costs. The expanded product offering allows the combined firm to reach a larger audience, deepen relationships with existing customers, and amortize marketing or distribution spend across multiple business units.

Economies of scope can therefore result in value that’s greater than the sum of the parts. Instead of being based on cutting costs, this is about expanding a company’s relevance in the market. As a result, it can often be more durable than pure economies of scale, and correspondingly harder for competitors to imitate.

3. Synergies

Synergies are typically described with the phrase, ‘one plus one equals three.’ The theory is that two companies working together in tandem can produce greater value than either could individually. This can take the form of cost savings, new revenue opportunities, or other means of enhancing the combined firm's competitive position.

An example is provided by Disney's acquisition of Lucasfilm. Lucasfilm was already a huge cash generator through the Star Wars franchise, widely recognized as one of the most valuable entertainment properties in the world. By itself, this had meant major revenue from movies, licensing, and merchandising, as well as a powerful fan following. By bringing Star Wars into the Disney fold, however, the company was able to multiply its impact and revenue.

Lucasfilm’s flagship property is now plugged into Disney’s global ecosystem of theme park rides and attractions, merchandise, streaming entertainment, and cross-marketing with other Disney brands. In other words, the deal transformed an already very valuable property into a growth engine that could power it in multiple new directions.

Many synergies are less visible to the public. Some include sharing a distribution network, consolidating research and development teams, or aligning data systems to better track and target customers. Others involve financial benefits such as increased borrowing power or more favorable tax structures.

The important thing to remember is that synergies don’t automatically materialize on their own. They have to be understood, planned, and executed. Otherwise, the “three” can quickly become a “two” - or even less.

Read more

Why You Should Focus Less on Cost Synergies During PMI

4. Opportunistic Value Generation

Not every acquisition is strategic. Value can be created from an opportunistic deal when the right deal presents itself.

The hallmark of these acquisitions is that the purchase price is less than the fair market value of the target company’s net assets. In other words, the buyer gets more than it pays for from day one.

Often, these companies will be in some financial distress. A buyer with more capital can step in, keep the business alive, and get the value of owning the assets or operations immediately, at a discount. In some cases, it might also mean being able to acquire IP, facilities, or talent for much less than it would otherwise cost to develop them organically.

It’s easy to see the appeal: immediate value creation without having to wait for synergies or lengthy integration efforts to take effect.

However, opportunistic acquisitions are not without risk. If the fundamental issues with the business are deeper than anticipated, or if market conditions continue to deteriorate, the “bargain” may quickly become a liability. The most favorable outcomes tend to occur when the buyer not only acquires the target at a discount but also has the means and strategy to stabilize and turn the business around.

“Bringing integration in early—before the LOI—is life-changing. It helps us plan, build trust with sellers, and hit the ground running on day one.”

- Stephanie Young

Shared at The Buyer-Led M&A™ Summit (watch the entire summit for free here)

5. Increased Market Share

One of the primary motives for undertaking M&A is to increase market share. By absorbing competitors or expanding into new territories, a company can quickly boost its presence in ways that would take years through organic growth. The larger the share, the more control a company has over pricing, customer loyalty, and long-term industry dynamics.

Historically, retail banks have considered their geographical footprint crucial to achieving market share. Branch networks lead to increased customer base, higher brand awareness, and improved economies of scale. The result in many countries has been a handful of powerful retail banks (known as the “Big Four” in the UK and the U.S. and the “Big Five” in Canada) that have emerged from decades of gradual consolidation.

Santander, for example, utilized acquisitions as a cornerstone of its overall business strategy, enabling it to grow from a relatively local Spanish bank into one of the world's largest retail banks.

This trend is not unique to banking. In all industries, a large market share can translate to better bargaining power with suppliers, fewer threats from new entrants, and a reputation for being the most stable brand in the eyes of customers. The risk, of course, is that the resulting market dominance could attract regulators or dilute the company’s ability to serve its customers effectively.

6. Higher Levels of Competition

The larger the company, in theory, the more competitive it becomes. A larger company may have access to more capital for investment and distribution, existing relationships with retailers, and stronger brand recognition. Theoretically, a bigger organization has the capacity to compete for more markets, more customers, and more influence.

Again, this is essentially one of the benefits of economies of scale: Larger firms have the benefit of spreading the fixed costs of manufacturing or delivering a product or service over a greater number of units, which can reduce the per-unit cost.

Companies may have the financial flexibility to price more competitively or reinvest in research and development, marketing, or other growth initiatives. Additionally, larger firms may be able to absorb economic downturns or supply chain shocks more easily than smaller competitors and can afford to have longer product development cycles.

Take the plant-based meat market, for example. Dozens of start-ups have already emerged, many with innovative product formulations and bold branding.

However, when a global heavyweight like Nestlé or Procter & Gamble enters the fray, the competitive dynamics change. Such corporations can invest millions of dollars in R&D, muscle out smaller brands on shelves, and benefit from economies of scale in sourcing, production, and marketing. Smaller players will be hard-pressed to compete, even if their ideas are not inherently inferior to those of the multinationals, primarily due to the competitive advantages of scale.

On the other hand, robust competition resulting from consolidation can lead to improvements in standards, a faster pace of innovation, and a higher rate of adoption of new products and services. Large companies should utilize their expanded resources to compete effectively, but should avoid abusing their size to homogenize or dilute the market.

7. Access to Talent

Talent is one of the most valuable assets a company can acquire, and in many sectors, it is one of the most challenging to source. Ask anybody in the recruitment industry where the biggest talent shortages currently are, and the answer will invariably be a variant of ‘people that can code.’

Why is this?

It’s partly the result of growing demand for digital skills driven by the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution. AI, automation, data analytics, and cloud computing have made technical know-how essential across sectors.

Additionally, much of that high-end talent is already employed by large Silicon Valley technology companies. Firms like Google, Apple, and Meta have the deep pockets, cachet, and career opportunities to attract and retain the world’s top engineers. Smaller firms rarely have the resources to compete.

M&A is a way to level the playing field. An acquisition is, by definition, also a people purchase. You take over not just the products and IP, but the engineers, designers, analysts, or executives who make a business run. It’s a way of “acquiring” new skills, culture, and innovation. Tech companies often do this in the form of “acquihires,” where the main attraction of a small company is its top-notch talent pool.

A classic example is Google’s 2014 acquisition of DeepMind. On paper, it was a deal for artificial intelligence research, but in reality, it was a deal for talent. DeepMind’s team included some of the world’s leading experts in machine learning and neuroscience, and bringing them into Google’s already impressive team advanced the company’s AI efforts by years.

Facebook made a similar play when it acquired Onavo, a small Israeli analytics startup, in 2013. The technology was useful, but what Facebook really gained was Onavo’s team of mobile analytics experts who helped the company sharpen its competitive advantage. These “acquihire” deals exemplify how M&A can serve as an express pass to world-class talent, allowing large organizations to acquire expertise that would otherwise take years to develop internally.

This benefit is not unique to software. Biopharma companies acquire biotechs to acquire their scientists and research teams. Manufacturers acquire smaller engineering companies to attract top talent.

It’s a logic that plays out in all sectors: size breeds more ability to attract and keep the best people. Scale is attractive not only for financial security, but career development, international mobility, and access to innovation. In many ways, M&A done strategically can be a shortcut to solving endemic talent shortages by acquiring the very people who will shape the company's future.

8. Diversification of Risk

Risk diversification is one of the less visible but more powerful motivations behind many mergers and acquisitions. The basic idea is that a company with a larger number of products, markets, or revenue streams is less susceptible to unexpected changes in one or more of those areas. By diversifying exposure across different segments, regions, or customer bases, the company becomes more resilient to market shifts or changes in consumer behavior.

This goes hand-in-hand with economies of scope: By having more revenue streams, it follows that a company can spread risk across those revenue streams, rather than having it focus on just one. Diversification also allows a company to better weather cyclical downturns, regulatory changes, or technology disruptions that may impact one division more than others.

Meta (formerly Facebook) is a case in point: when Facebook’s core platform began to decline, especially among younger users, the company was able to rely on Instagram and WhatsApp (two of its largest acquisitions) to maintain engagement and advertising revenue. Both platforms serve different audiences and use cases, and both have continued to grow, providing Meta with multiple avenues to reach users and advertisers.

Risk diversification through M&A is not limited to tech companies. Energy companies, for example, may acquire renewable energy businesses to hedge against fluctuations in oil prices. Food and beverage companies may diversify by acquiring health-focused brands to offset changing consumer preferences. Industrial companies may diversify by acquiring businesses in related sectors to smooth out the impact of cyclical demand.

When one revenue stream falls, an alternative stream of revenue may hold, or even pick up, diversifying the acquiring company’s risk in the process.

Of course, diversification is not a guaranteed success strategy. Over-diversification can dilute leadership, confuse the brand, and siphon resources from the core business.

The less related the acquisitions are, the more difficult it becomes to manage them effectively or to extract meaningful synergies. Some conglomerates have made this mistake in spades, becoming so broad that coordination, focus, and profitability all suffered.

Balance is key. Diversification is most effective when new lines of business have natural synergies with the existing ones (sharing customers, technology, or capabilities) so that the company gains stability without losing direction. The goal is not to have a stake in everything, but to build resilience where it makes strategic sense.

9. Faster Strategy Implementation

Mergers and acquisitions may be the best way to make a long-term strategy become a mid-term strategy. Suppose a company has a long-term strategic objective, such as entering a new market, launching a product, or building a new capability. In that case, there are usually two options to get there: grow organically (slowly) or acquire an existing business (much faster). M&A can accelerate five- and ten-year plans into one- and two-year transformations.

Expansion into a new geography offers a simple example. An organization that wants to enter the Canadian market could open offices, hire teams, establish distribution channels, and win customers over the course of several years. Or it can buy a local player that already has those assets: an established customer base, regional expertise, and brand awareness, enabling it to compete from day one.

The same principle holds true for innovation. Instead of investing years in R&D to create new technologies or products, a company can acquire startups or niche players with ready-made solutions and talent. Pharmaceutical companies routinely acquire biotech firms with promising drugs in their pipelines. Large technology companies use M&A to fast-track innovation, gaining instant access to patents, data, and expertise.

In many industries, speed is the ultimate competitive advantage. M&A enables companies to leapfrog competitors, shorten time-to-market, and seize opportunities (or counter threats) more quickly. It’s not without cost or risk. Deals can be expensive, and integration is hard work. But for firms under pressure to transform, the pace and certainty of buying can be far more attractive than the risks and delays associated with building.

One such example is Google’s acquisition of Android in 2005. Google had no presence in the mobile operating system market at the time, and building one from scratch would have taken years. But by acquiring Android, Google instantly acquired the foundation of what would become the world’s most widely used mobile platform, something that would have taken at least a decade to do on its own.

Not every Google acquisition has been a blockbuster, but the company has repeatedly shown how strategic M&A can accelerate innovation and open new growth frontiers. From YouTube to Waze, Google has used acquisitions to turn long-term ambitions into near-term success.

Another example is Apple’s acquisition of Beats in 2014. Apple could have spent years building its own premium headphone line and music streaming service from the ground up, but by acquiring Beats, it achieved both in a hurry. The deal gave Apple not just a strong hardware brand, but also the expertise and technology that would become Apple Music.

These cases illustrate how acquisitions can compress the strategic clock, helping companies accomplish in a few years - and in some cases, even a few months - what might otherwise take a decade.

10. Tax Benefits

Tax savings are a potential motive for an M&A deal, but are rarely a primary driver in most deals. That said, they can be very attractive, and are a particularly strong rationale for cross-border M&A among multi-national companies. By merging with or acquiring a business in a lower-tax country or with a more favorable tax regime for foreign income, a company can improve its after-tax earnings in a material way.

This concept is known as tax inversion. In a tax inversion, a company from a high-tax country buys another with a legal address in a lower-tax jurisdiction and then relocates its headquarters. The company’s operations might not change much at all, but the tax benefits can be significant.

Inversions of this kind gained a lot of attention in 2016 when U.S. drug company Pfizer sought to merge with Allergan, an Irish company, in a $160 billion deal. The move would have effectively relocated Pfizer’s headquarters to Ireland, where it would have been subject to a much lower corporate tax rate than in the U.S. In response, the U.S. government moved to restrict such inversions and the merger was ultimately called off.

Tax benefits that do not rise to the level of full inversions can be entirely legitimate. A profitable company might buy another with tax loss carryforwards, for example, enabling it to use past losses to offset future taxable income. In other situations, deals might allow better utilization of deductions, depreciation schedules, or intercompany financing structures.

Tax benefits have come under much more scrutiny from regulators in recent years. In many countries, rules are in place to ensure that deals are not motivated primarily by tax benefits. For most acquirers, this means that tax benefits are a bonus to be added to the valuation if present. But done well, they can add value. Rarely are they a deal driver on their own.

11. Financial Engineering and Capital Structure Optimization

Financial engineering, while not the most heralded aspect of mergers and acquisitions, can be a critical element of a successful deal. Through M&A, companies often aim to optimize their financial structures to strengthen balance sheets, reduce costs of capital, and enhance shareholder value. This facet of M&A can involve various tactics and strategies, collectively referred to as financial engineering and capital structure optimization.

Financial engineering involves using various financial instruments and strategies to create a more favorable capital structure. This can include optimizing the mix of debt and equity used to finance the acquisition, as well as using leverage and financial engineering to reduce the cost of capital and improve the overall financial performance of the combined company. For example, a company may be able to take on more debt after a merger or acquisition if the new entity has a lower risk profile, which can reduce its overall cost of capital.

One example is the United Technologies and Raytheon merger in 2020, which brought together two industry leaders to form one of the world’s most advanced aerospace and defense companies. Prior to merging with Raytheon in an all-stock transaction, United Technologies had spun out Otis and Carrier as independent public companies. The spin-offs enabled the combined company to have a much leaner balance sheet and more targeted capital allocation priorities upon closing.

Separately, the move created more focused entities and allowed the aerospace defense merger to occur with a clearer view of the combined Raytheon Technologies' capital strategy. The overall process, first to spin the non-core entities, then to merge the core businesses, was also part of an intentional financial engineering strategy to optimize the leverage, credit profile and investor fit.

Capital structure optimization involves reconfiguring the company's capital structure after the merger to achieve a more efficient balance between debt and equity. This can be done by refinancing existing debt at a lower cost, using the assets of the acquired company to obtain better borrowing terms, or issuing new equity to reduce the company's leverage. An optimized capital structure can improve financial flexibility and free up capital for future investments, dividends, or share buybacks.

In some cases, M&A can also unlock value that is trapped in the capital structure of one of the companies involved in the transaction. For example, a company may have underutilized assets or cash reserves on its balance sheet that can be put to better use in the combined entity. Private equity firms are particularly skilled at this kind of financial restructuring, using leverage and post-acquisition refinancing to enhance returns without necessarily changing the core operations of the business.

Of course, financial engineering isn't without limits. Aggressive use can lead to overleveraged companies sensitive to interest rate hikes or market downturns, as was seen in some high-profile leveraged buyouts (LBOs) that unraveled amid economic shocks, such as Toys “R” Us and Energy Future Holdings. The best deals treat the capital structure as a long-term asset, not a short-term gimmick.

Done well, financial optimization through M&A can give companies more stability, lower capital costs, and a stronger platform for growth. Done poorly, it turns balance sheets into ticking time bombs. The difference usually comes down to discipline, timing, and an honest assessment of what the combined company can sustainably support.

12. Value Chain Integration (Vertical Synergies)

Value chain integration, or taking control of additional parts of the production, distribution, or supply process, is another key source of M&A value. Companies with greater control over the value chain have more stability, efficiency, and pricing power.

These “vertical synergies” can take one of two forms: going up the chain (backward integration, such as acquiring suppliers or manufacturers) or going down the chain (forward integration, such as acquiring distributors, retailers, or platforms closer to the customer).

Backward integration can help a company control important inputs and reduce dependency on suppliers. For example, if a car manufacturer acquires a battery producer, it can secure a steady supply of batteries, reduce costs, and protect its intellectual property. It also mitigates the risk of price volatility or supply disruptions, which can severely impact companies that are dependent on external suppliers.

Forward integration brings a company closer to its end customers. A common example is a producer acquiring its distributors or retail channels, which allows it to gain greater control over the brand, customer experience, and margins. This is frequently seen in consumer goods, energy, and technology sectors, like Apple opening its own retail stores, or Netflix going from distributing DVDs to producing its own shows and distributing directly to consumers.

Vertical synergies often result in operational efficiencies, improved quality control, and better data transparency across the supply chain. A company that controls more of the value chain can optimize from the ground up, improve alignment of incentives, and remove some of the friction between partners.

On the other hand, vertical integration can also involve tradeoffs. It can lock up capital in activities that aren’t core to the business, make a company less nimble, and run into antitrust issues if the merged company has too much power over a particular market. The most successful vertical mergers are often more discerning, choosing to integrate only the parts of the chain where there’s a clear strategic advantage and value-add, instead of just acquiring for the sake of ownership.

13. Brand and Reputational Benefits

In mergers and acquisitions, what you gain isn’t always tangible; sometimes it’s intangible. A powerful brand can be the most valuable asset a company acquires. It can even be worth more than the business itself. A well-executed M&A can increase credibility, widen customer trust, and enhance market perception far more quickly than organic growth ever could.

In some cases, companies seek out acquisitions that will bring an already respected brand into their fold. It’s hard to start from scratch in a new market with a new, unproven name; buying a company that already has a loyal following, good reviews, and brand recognition eliminates that challenge right off the bat.

This is especially true in consumer goods industries, where emotion plays as much a role as the quality of the product itself, but it holds true in B2B businesses such as financial services, consulting, and tech, where trust and reputation are everything.

Unilever’s acquisition of Ben & Jerry’s is a good example. Beyond a highly profitable product line, Unilever also acquired a brand with social and ethical values as well as cultural resonance. Instead of watering it down, Unilever doubled down on Ben & Jerry’s identity, leveraging the halo effect and adding international scale and operational expertise. It created not just financial but reputational upside.

Of course, there are risks when it comes to co-branding identities. If corporate values don’t match up or the integration process is bungled, reputations can be damaged on both sides. Consumers can see when authenticity is lost. The best acquirers understand what made the target brand great and preserve its independent voice while making it part of a bigger family.

14. Cross-Selling and Up-Selling Across Lines

Cross-selling and up-selling opportunities are some of the most straightforward paths to M&A value creation. By merging two complementary businesses, each gets immediate access to the other’s customer base, providing ready-made avenues for additional revenue that don’t require large new customer acquisition costs.

Cross-selling involves marketing one company’s products or services to the customer base of the other. If a logistics company acquires a warehousing business, it can offer integrated supply chain solutions to existing clients who previously only purchased one service or the other.

Upselling focuses on deepening each customer relationship by adding higher-value versions, bundled offerings, or extended contracts that were not previously available or feasible without the merger.

For example, Salesforce acquired Slack, not simply as a communication platform but as a way to integrate its CRM software more deeply into daily workflows. Users of Slack benefit from a new point of exposure to the Salesforce ecosystem, while existing Salesforce customers gain access to Slack’s collaboration features. This two-way cross-selling synergy adds new revenue paths on both sides of the deal.

Similar synergies are seen across sectors, from finance to healthcare. Banks acquiring insurance companies can cross-sell financial protection products, while tech companies acquiring cybersecurity startups can upsell security features to existing customer relationships. These multi-product relationships deepen customer loyalty and make it more costly to switch providers.

15. Regulatory or Government Incentives in Certain Geographies

Strategically motivated M&A is not always a purely commercial calculation; in some cases, the government can help to tilt the economic case for a deal. Policymakers in many countries actively promote M&A as part of their national agenda, whether it is to create jobs, support innovation, drive sustainability or bolster industrial competitiveness. As a result, certain mergers and acquisitions can become financially compelling or even operationally necessary.

The incentives can take different forms, including tax incentives, grants, subsidies or other subsidies for deals that invest in priority sectors, such as green energy, manufacturing or high-tech. Several European countries and U.S. states, for example, have created tax incentives for clean-energy M&A that can build green infrastructure or local production.

Cross-border deals may also qualify for preferential treatment in the form of trade or investment treaties, which can result in lower tariffs or smoother regulatory approvals if the target aligns with the national interest.

In emerging markets, M&A can be a route to gain access to special economic zones (SEZs) or reduced import tariffs if the acquirer agrees to hire and train local staff or build local production facilities. These programs give multinational corporations an opportunity to enter new markets with a lower cost base, and to share some of the benefits with the host country.

There can also be regulatory benefits where governments are more supportive of industry consolidation to create economies of scale and improve oversight. The banking sector is a good example of this, with many governments encouraging mergers in order to bolster their national champions. Regulators have sometimes even actively facilitated the acquisition of underperforming firms during a downturn to protect jobs and instill confidence in the market.

Incentives are generally not given lightly by governments, and they often come with certain conditions attached, such as local content requirements, transparency obligations or restrictions on share ownership by foreign investors. A tax or regulatory-driven M&A transaction, therefore, needs to take into account these additional conditions as a cost in addition to the benefits.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most important benefit of mergers and acquisitions?

There is no single "most important" benefit, as the primary goal varies by company strategy. However, accelerated growth and competitive advantage are often the overarching drivers. For some, it might be gaining market share quickly; for others, it could be accessing new technology or talent that would take years to develop organically.

What is the difference between economies of scale and economies of scope?

Economies of Scale refer to cost advantages gained by increasing the volume of production or operations. The average cost per unit decreases as output grows (e.g., bulk purchasing discounts, spreading fixed costs).

Economies of Scope refer to cost advantages gained by increasing the variety of products or services offered. Leveraging a core platform or infrastructure to serve additional markets at a low incremental cost (e.g., Meta using its ad platform across Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp).

Are M&A synergies guaranteed?

No, synergies are not guaranteed. They are potential opportunities that depend on effective deal structuring, timing, and, most critically, successful post-merger integration (PMI). Many deals fail to realize projected synergies due to cultural clashes, poor planning, or unexpected market changes.

How long does it typically take to realize the benefits of an M&A deal?

The timeline varies by benefit type. Cost synergies from consolidation (such as overhead reductions) may appear within 12-24 months. Revenue synergies (such as cross-selling) often take 2-4 years to fully develop. Strategic benefits like entering a new market are immediate, but profitability from that move takes time.

How can a company ensure it captures the acquired company's brand value?

Successful brand integration requires preserving the core identity and value proposition that made the brand strong while leveraging the acquirer's resources for scale. This often means operating it semi-autonomously, avoiding brand dilution, and clearly communicating the strategic rationale to customers.

What role does post-merger integration (PMI) play in achieving these benefits?

PMI is the single most critical phase for realizing M&A benefits. A disciplined PMI process is where synergies are tracked and captured, cultures are merged, systems are integrated, and the strategic vision is operationalized. A great deal with poor integration will likely fail to deliver its promised value.

Key Takeaways

- M&A can accelerate growth and competitive advantage by unlocking strategic, financial, and operational value that would take years to achieve through organic expansion.

- The real benefits of M&A are never guaranteed and depend heavily on deal structure, timing, and disciplined post-merger integration.

As this list shows, well-planned and executed acquisitions can deliver a wide range of benefits. The better structured and executed the deal, the more likely these advantages are to materialize.

Learn more about M&A best practices in the video below:

For anyone planning an acquisition strategy, it’s essential to consider which of these benefits align most closely with your objectives, and let those motives guide your approach to buying.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)