During 2022, global venture capital deals crossed the $225 billion barrier and are on track to beat the 2021 record of $330 billion.

The overall venture capital dollar volume is also growing. The growth of venture capital deals would be remarkable in 'normal’ times. Set against the backdrop of an

ongoing global pandemic, we can see that Venture Capital funding is now truly a mainstream form of financing and a focus on startups has earned a place in the public

consciousness. What makes low-profit companies so valuable? For example, in 2022, investors valued Uber at $85 billion, despite posting losses of $149 million in 2021

(its most successful year to date).

How Venture Capital Firms Work

Note: This article uses the terms ‘startup’ and ‘early-stage company’ interchangeably, but most of the companies that venture capital firms work with are considered ‘early-stage companies.’

Early-stage companies looking to raise startup capital are companies with a clearly defined business model, a minimal viable product (MVP) in place, and possible funding from friends and family.

Essentially, early-stage companies are in the right position to look for venture capital funding to commercialize an idea. Companies approach venture capital firms with a pitch deck, usually a PowerPoint document of around 15 slides, that outlines their growth vision for a company.

Every pitch deck has a ‘sources and uses’ slide, where the startup founder shows the venture capital firm why their money is needed, how it will be spent, and how it will contribute to the growth vision. This is the basis of the deal terms.

Read also

The Essential Guide to Capital Raising

Characteristics of firms being funded by venture capital

Before launching into typical deal terms offered by Venture Capital firms, a recap on some of the characteristics of startup companies is worthwhile. Understanding these is crucial before seeing how deals are structured.

- Low Revenue and Cash Flow: Almost all startups will have some sales to their name before approaching venture capital firms to show that they have a market. Typically, the sales cash flow will be very low and not enough to pay salaries (startup founders typically eschew a personal salary for a few years to show their commitment to the project).

- Little Track Record: Although a maturing venture capital scene means that there are now serial startup founders, most startups are no more than a year or two old when they are looking for venture capital funding. There’s no way for investors to look through years and years of annual statements.

- Overly optimistic projections: Every startup founder thinks they’re going to change the world with their company. Venture capital firms know this and factor it in during projections by dividing the serviceable obtainable market (SOM) calculated by the startup founder by three or four.

- No established market: Unless the startup company copies others in the field (while adding a few tweaks on price, geography or target market), there’s a good chance that the market will be hard to calculate. Take Airbnb as an example - it has 5.6 million listings on its site. But as a concept that had never been tried before, how would anyone have arrived at that number?

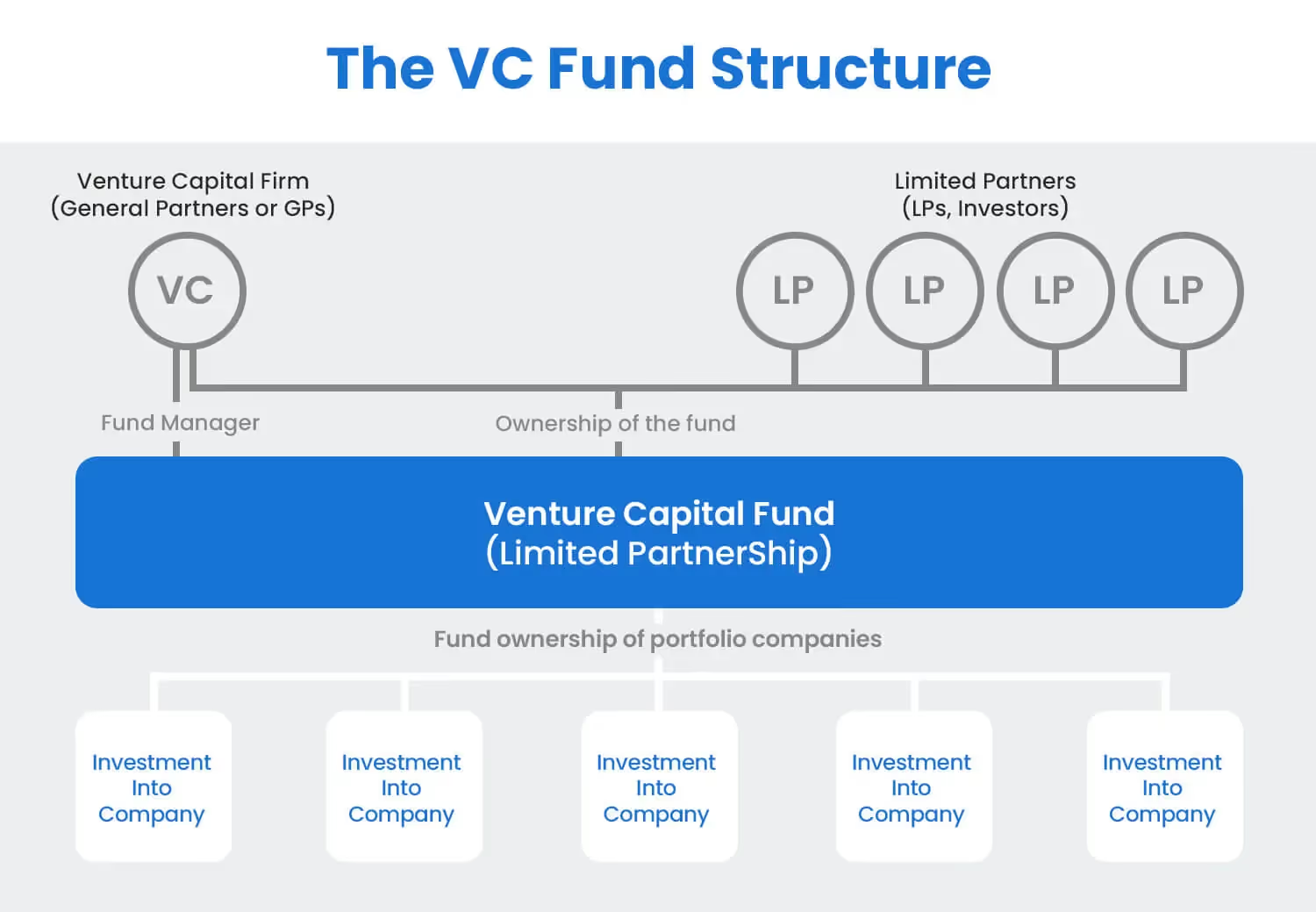

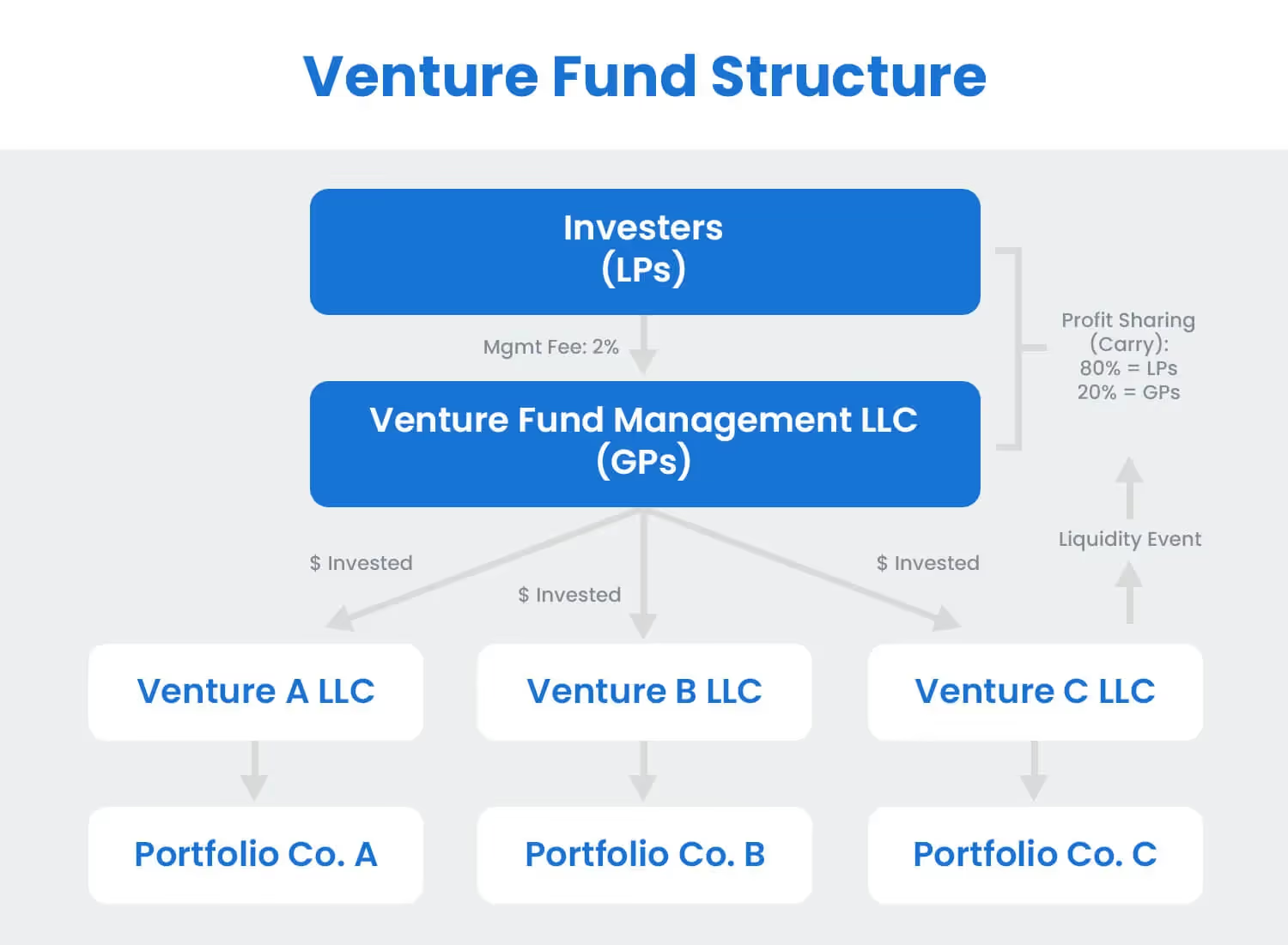

How to Structure a Venture Capital Deal

Start with establishing value for the startup. As mentioned in the previous section, startup founders have a naturally optimistic attitude which sometimes leads them to

extravagant valuations compared to reality. The business model of most venture capital firms is to invest in several different startups at once in the expectation that the

stellar returns of one will more than compensate for the losses of the others.

Thus, the venture capital environment is volatile in terms of the returns generated by businesses, and the covenants in contracts should reflect this. Venture capital firms

need to protect themselves on the downside and buy in as much as possible on the upside. A typical deal structure goes something like the following:

1. A venture capital (VC) fund invests $5 million in exchange for 30% of preferred equity. The fact that this is preferred equity is important: it usually includes a number of the provisions that protect the VC firm on the downside in the short- and long term.

These include:

- A liquidation preference that gives the VC firm absolute preference over common shareholders until their $5 million is returned (similar to how creditors receive preference).

- Disproportionate voting rights that enable the VC firm to direct the startup’s strategy. This could include everything from capital investments to decisions around later rounds of capital raising.

- Anti-dilution clauses (‘ratchets’) that ensure the equity share of the VC firm is not diluted, regardless of how later rounds of financing pan out.

2. There are also upside provisions that the VC firm will seek to benefit from should the startup achieve some of the projected success.

These include:

- An option to acquire a pre-agreed-upon number of shares in the future at a pre-agreed-upon price, enabling the VC firm to acquire more stock at a discount if the startup does well (even if other VC firms come along and offer much higher amounts for the equity).

- Assurances about the exit strategy - i.e. the VC firm will usually have a clause that determines when the startup has to liquidate its shares, through an industry sale, a sale to another VC firm, or an IPO.

Other provisions, common to all VC deals include the following:

- The VC firm will include the right to elect the majority of the startup board's directors, enabling it to maintain control over the management of its day-to-day management.

- Rights to access all of the startup’s internal documents, including financial statements, and documents relating to all other transactions.

Conclusion

Those with experience in drafting regular share purchase agreements (SPA) will see that there are large similarities between SPAs and the deal structures agreed with VCs.

The growth of this industry, both in the US and elsewhere, suggests that deal structures have matured to the extent that they now suit entrepreneurs and investors.

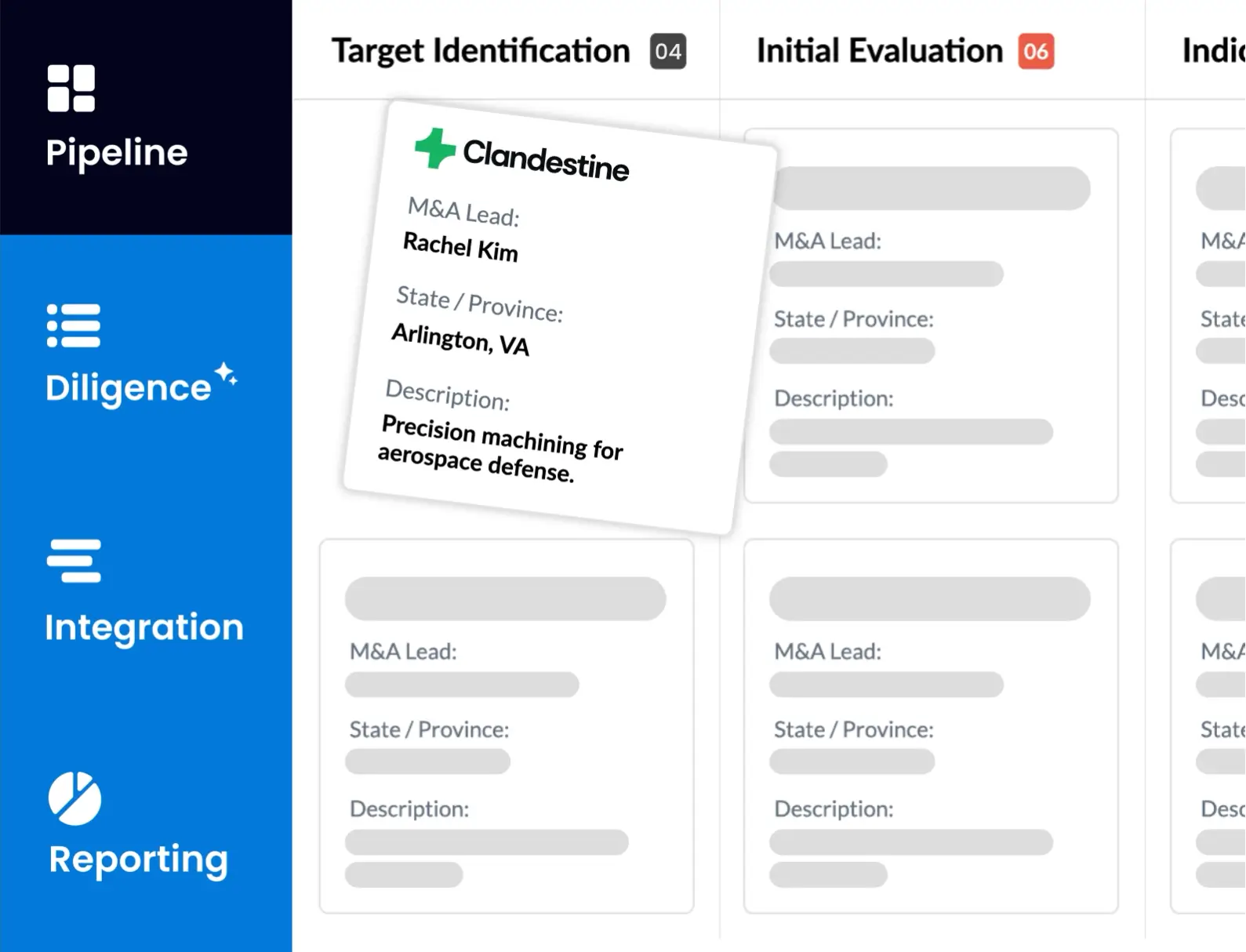

If your company is considering a VC investment, talk to FirmRoom about how our virtual data room software can ensure the process is frictionless.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)