Tens of thousands of M&A transactions are conducted globally every year and yet, usually only a few dozen obtain any media coverage.

What of the rest?

Well, a good proportion of these deals are either tuck-in or bolt-on acquisitions. These are smaller deals that are less attention-grabbing than the so-called mega-deals.

Unlike many of the larger deals, they’re also more often value accretive.

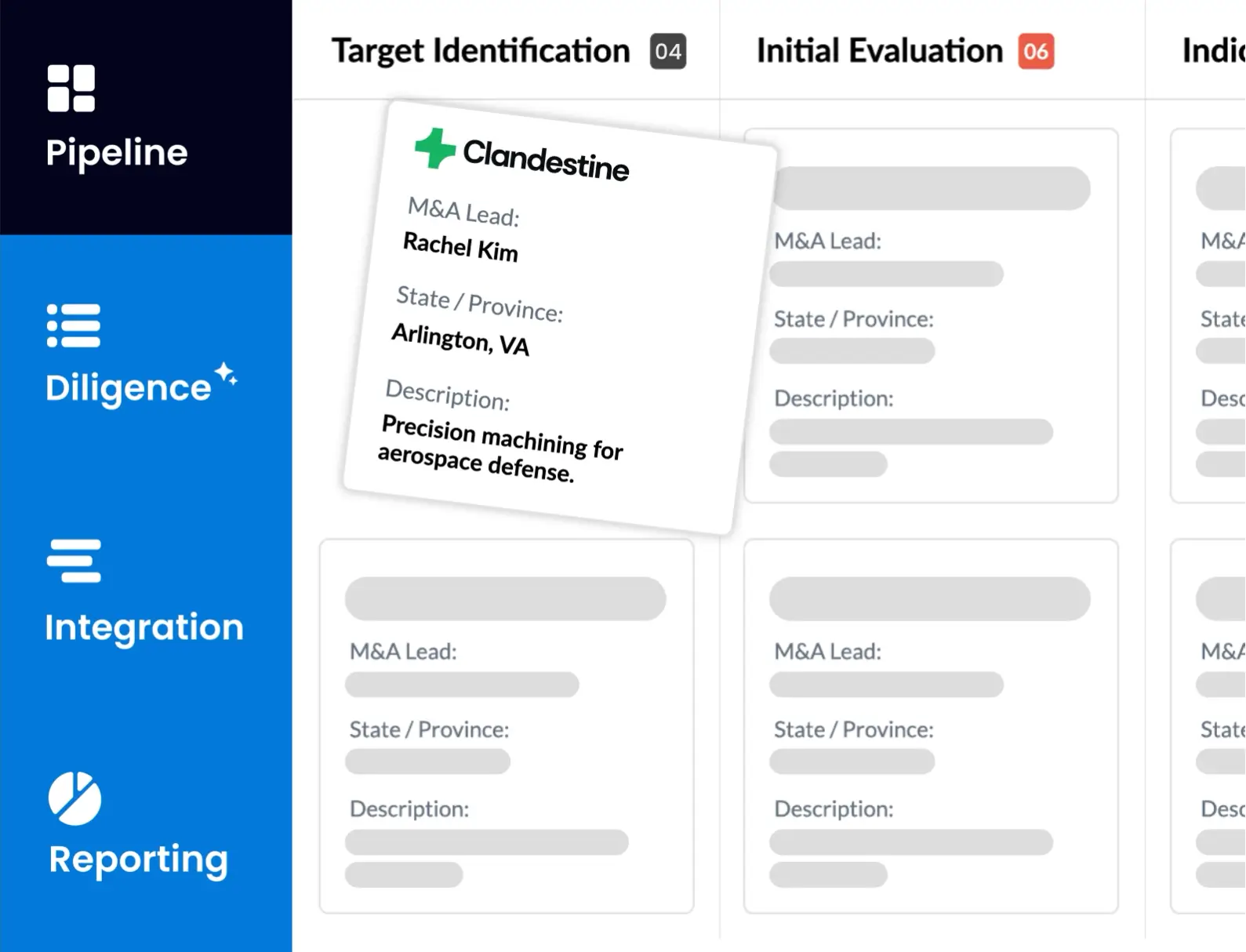

We at DealRoom help many companies organize their M&A process and in this article, we look at both tuck-in and bolt-on acquisitions and the value that they can unlock for companies which are active in M&A.

Let's start with definition, It will help to understand the difference between ‘tuck-ins’ and ‘bolt-ons’ from the outset.

What is a Bolt-on Acquisition?

A bolt-on acquisition is the expression used when a larger company acquires a significantly smaller company with a strategic motive. The strategic motive here is important: although bolt-on acquisitions are usually cash-flow generative, their income is usually small enough relative to the acquirer that it’s not the main motive for the acquisition.

%20(1).jpg)

Private equity companies typically employ bolt-on acquisitions to add value to their portfolio companies before disposing of them. These are usually synergistic (i.e. both companies benefit from the transaction), and may add one or all of:

- new customers,

- new product lines,

- new geographies

- or even attractive intellectual property to the acquiring company.

One more example could be a Shell's Oil Company (Shell) acquisition of MSTS Payments and its Multi Service Fuel Card business that provides Shell with the necessary shell business gas card technology, business infrastructure and talent to accelerate the growth of its global commercial cards business, Customer Value Propositions (CVPs) and services.

Why a Bolt-on Acquisition

Bolt-on acquisitions, (sometimes referred to as ‘roll-up acquisitions’), tend to have all of the same motivations as larger M&A transactions, among them an increased product or service portfolio, an expanded geographic footprint, enhanced technological capabilities and more.

The major difference with a bolt-on acquisition is that, being smaller, there tends to be less risk involved in the transaction.

And the cumulative effect of making several bolt-on acquisitions can allow a company to grow at speed in a relatively short period of time.

What is a Tuck-in Acquisition?

Tuck-in acquisitions are largely the same as bolt-on acquisitions with the main exception being that the smaller company is completely absorbed into the buyer: whereas many bolt-on acquisitions may retain their names and identities, a tuck-in acquisition loses its corporate identity and structure to become an indistinguishable part of the larger firm.

.jpg)

Can a Smaller Company Buy a Larger Company?

There is nothing to stop a smaller company acquiring a larger company if it has enough cash or an attractive enough structure to convince the larger company’s shareholders to sell out.

This is usually achieved through leverage or with deferred shares.

A good example can be seen in the acquisition of Land Rover Jaguar by Tata Motors, a small relatively unknown automotive brand (outside of India, at least) taking over an auto industry stalwart.

Read also: 11 Powerful Acquisition Examples (And What We Learned from Them)

Examples of Bolt-on and Tuck-in Acquisition

To better understand the distinction that exists between a bolt-on and a tuck-in acquisition, it’s worthwhile to look at two such deals, both undertaken by the same company: Facebook.

Facebook has made dozens of tuck-in acquisitions, all of which were ‘shut down’ (read: ‘tucked in’) shortly after the acquisition was made.

An example was TheFind.com, an online shopping discovery platform. Facebook acquired it in early 2015, before shutting it shortly afterwards. In 2016, Facebook launched Facebook Marketplace: TheFind had been tucked in.

But there are also a few high profile examples of when Facebook acquired bolt-on acquisitions.

The most well-known example is probably Instagram, which it acquired in 2021 for $1 billion.

Unlike the example of TheFind.com, Instagram maintains its original identity and could be construed as a completely independent company, making it a bolt-on acquisition.

Examples of Bolt-on Acquisition Strategies

As mentioned, private equity companies commonly apply bolt-on acquisition strategies for their portfolio companies.

The larger company, referred to as the “platform” company, acquires smaller, complementary assets which add value before the divestiture.

This type of acquisition is extremely common among consumer goods companies, where a new resource such a food category or brand (to take two examples) can add clear value to the platform.

This is as true for independent consumer goods companies as it is for private equity companies The ubiquitous Coca-Cola fridge that adorns the vast majority of food retailers in the world contains an assortment of waters, juices, energy drinks and Coca-Cola’s main line of products.

Invariably, these products started out as independent brands before being acquired by Coca-Cola. (or ‘bolted on’ to the main brand, if you will).

This is a long-held strategy of Coca-Cola that goes back over half a century. The well-known Minute Maid juice brand was acquired in 1960, for example.

The strategy continues today, with the company invariably making purchases of popular juice brands in countries, complementing its main lines. Another example is provided by its 2014 acquisition of Monster Beverages, producer of Monster energy drinks, which gave Coca-Cola access to a fast-growing market.

A further example - although this time in home heating - is provided by the Irish company, Glen Dimplex.

Glen Dimplex has used a bolt-on acquisition strategy consistently over the course of 50 years to become the largest home heating company in the world by revenue, despite starting as a small, independent manufacturer with no ascertainable competitive advantage over any of the other players in its industry aside from a well-composed M&A strategy.

Read also

How to Acquire a Company in 8 Steps [Useful Guide]

Examples of Tuck-in Acquisitions Strategies

Tuck-in acquisitions are more seen in the energy and technology sectors, where either a resource (such as upstream or downstream assets) in the case of the energy companies or new capabilities (such as expertise or intellectual property) in the case of the technology companies.

These acquisitions then become almost completely absorbed within the larger company, usually with very little way to an outsider looking in to know if the acquisition was a success or not.

One of the most well-known (not to mention, successful) tuck-in acquisition strategies is that which is employed by Apple.

Apple makes enough acquisitions every year for them to warrant their own wikipedia page. The example of Apple is a good illustration of a tuck-in strategy at work.

Note how many of the companies it acquires are never ‘heard of’ again; they simply become part of Apple. Interestingly, the Wikipedia entry for its acquisitions even has a “derived product” column, showing which Apple product the acquisition ultimately contributed to.

Furthermore, it’s a reasonable bet that of all the transactions listed every year on transaction databases like CapitalIQ, the biggest cohort of deals by industry is in one of energy, minerals or hospitality.

Why?

Because the biggest firms in these industries are constantly acquiring new resources - oil wells and small exploration companies in the case of energy companies, mines (and sometimes mining technology) in mineral exploitation companies and portfolios of properties in the case of hospitality companies.

In all three cases, the assets are usually ‘tucked in’ to become part of the acquirer, becoming a footnote in corporate history.

Read also

Share Acquisition vs Asset Acquisition: Which is Better?

The Benefits of Bolt-on and Tuck-in Acquisitions

The main benefit of both types of acquisitions outlined is that they can be thought of as small, relatively low-risk additions to a bigger company.

Over time, the compounding effect of adding so many value-generating assets is that the acquirer’s value should have grown significantly.

Other benefits include:

- It’s typically easier to integrate smaller companies than larger ones

- There’s a bigger universe of smaller companies to choose from

- Smaller companies are often cheaper, not just in absolute terms, but in terms of multiples (i.e. price to EBITDA) making them more accretive to value

- These acquisitions offer a fast way to allow a company to grow geographically

The Risks of Tuck-In and Bolt-On Acquisitions

The risks for both tuck-in and bolt-on acquisitions are largely the same as those for any acquisition, albeit usually on a smaller scale.

Although their names suggest that these types of acquisitions can simply be added onto a company without any form of integration, that isn’t the case. And likewise, smaller size doesn’t preclude the requirement for extensive due diligence.

All that said, the risks of tuck-in acquisitions are:

- Losing the company’s internal identity, brand awareness and customer loyalty.

- Loss of any sell-on ability for the acquisition.

- Inability to check progress of acquisition ‘lost’ within the larger corporate entity.

The risks of bolt-on acquisitions are:

- The company risks losing focus by slowly becoming a conglomerate.

- Managers struggle with understanding what should and shouldn’t be integrated.

- Sales of the bolt-on acquisition may be cannibalizing those of the larger corporate entity.

Conclusion

Bolt-on and tuck-in acquisitions offer a proven method for companies to add value over a longer period of time.

Although many appear insignificant at the time of acquisition - particularly in terms of their financial results - the continued addition of their resources and capabilities allows the buyer to grow at a rate above and beyond what would be possible organically.

It should come as no surprise then, that both are strategies which have been employed by almost all of the world’s biggest corporations at some stage in their history.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)