Guide to Mergers & Acquisitions: M&A Meaning, Types, Examples

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are a $3.5 trillion activity that changes the long-term trajectory of careers, companies, and industries. Outside of an IPO - and even that is arguable - an M&A transaction is the largest corporate action that any company can take in its lifetime.

Outside of startups, there is not a billion-dollar company in existence that has not participated in at least one M&A activity. Therefore, there is simply no excuse for being uninformed about what goes on in this industry.

At DealRoom, we are deeply involved in the M&A space and have put together the following guide as a primer for those looking to learn more.

What are Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A)?

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is the process of combining two or more companies through various types of transactions. Despite the name, M&A encompasses more than just buying or selling a company. After all, there are other ways to combine companies together without any party giving up ownership. Let’s look at some of the most common types of M&A.

Different Types of Mergers & Acquisitions

1. Mergers

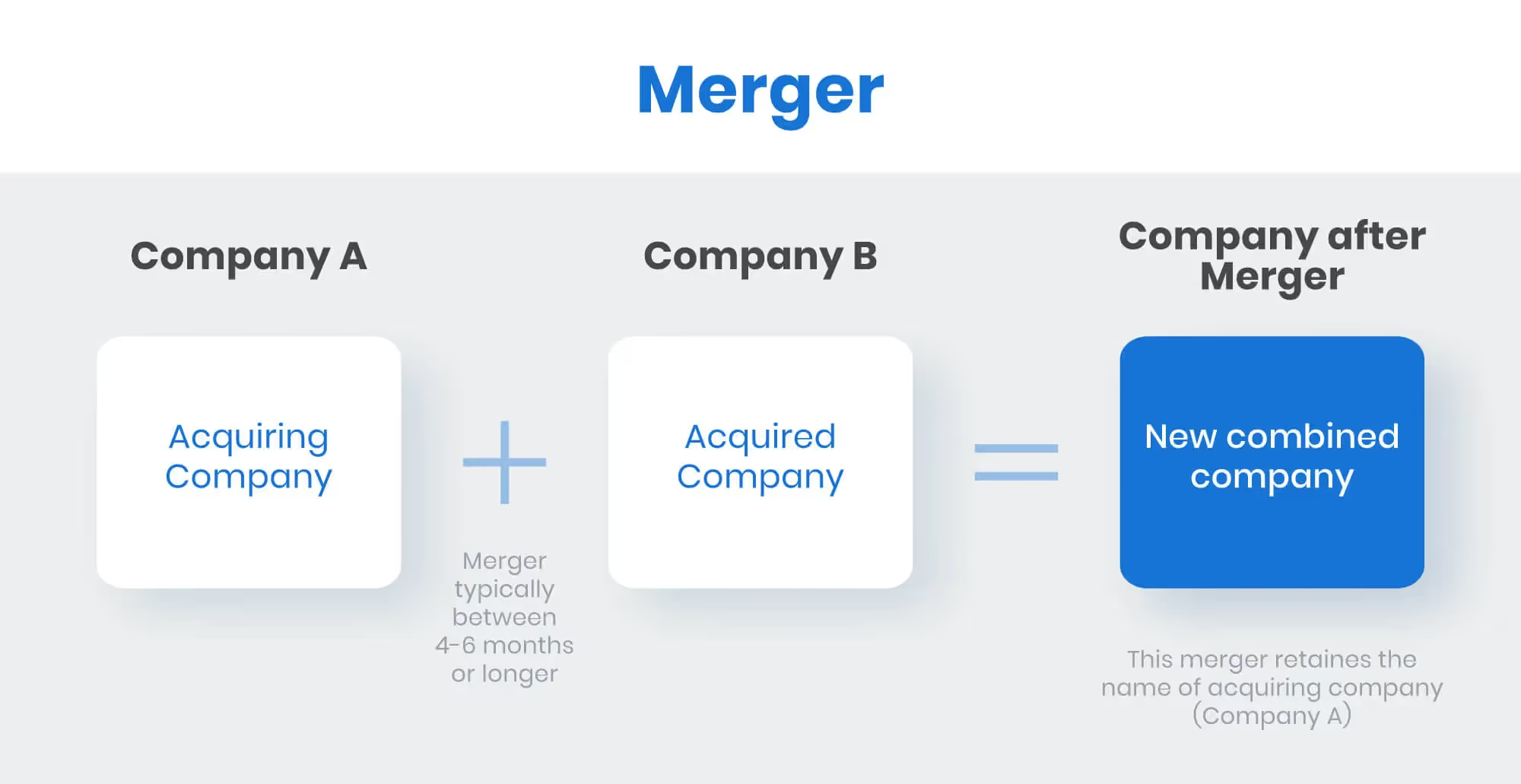

A merger is a corporate strategy that combines two separate business entities of roughly the same size into a single company, thereby increasing their financial and operational strengths.

Unlike an acquisition, corporate mergers are mutual, and both parties feel they will benefit from the transaction. Typically, in a merger of equals, no massive cash payment is involved. Most of the payment is made through the stock exchange, where shareholders of both companies receive shares in the newly formed company in proportion to their existing shares.

2. Acquisition

An acquisition is the purchase of the entire company or a particular asset of the target company. This involves payment to the seller and the transfer of ownership to the buyer upon completion of the transaction. To achieve successful acquisitions, the M&A process typically involves strategic deal sourcing, thorough due diligence, and seamless integration post-close.

3. Reverse Merger

This is a less popular but very effective way for private companies to go private. In a reverse merger, the private company buys most of the shares of a public shell company and then merges with it.

4. Joint Venture

Joint ventures are mutual agreements between parties to pool their resources and expertise together to pursue a specific goal. A distinct characteristic of this agreement is that the parties will establish a new company or entity, which will operate independently of the parent companies.

The perfect example of a joint venture is the agreement between Sony and Ericsson in 2001. They joined forces to create Sony Ericsson with the goal of dominating the mobile industry, leveraging Sony's expertise in consumer electronics and Ericsson’s strength in telecommunications.

5. Strategic Alliances

Strategic alliances are similar to joint ventures, with one major difference: They don't form a separate entity and operate independently.

A very current and popular example of this is the agreement between Toyota and Subaru for the development of the Subaru BRZ and Toyota GT86. For these particular vehicles, they both leveraged Subaru’s expertise in engine performance and Toyota’s capabilities in manufacturing and design.

6. Partnerships

Partnerships are very similar to joint ventures, but they differ in their structure, purpose, and duration. Partnerships are not restricted to a specific goal but rather run a long-term business, sharing profits and liabilities. Additionally, partnerships don’t have a fixed duration and can last indefinitely.

The table below breaks down the various types of mergers and acquisitions, their primary purposes, the impact on ownership, and provides examples or use cases.

Different Types of M&A Strategies

In M&A, it’s not as simple as buying or merging with another entity. Various strategies behind it will directly affect how the two companies integrate with each other. Understanding them will result in better integration and increase the chances of success of the mergers and acquisitions. Here are the different types of M&A strategies.

1. Horizontal M&A

A horizontal merger and acquisition combines two companies that provide the same service or product to final customers. In short, they are direct competitors that are merging to form a single entity, thereby increasing their market share. These transactions are heavily regulated by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to prevent monopolies and protect consumers from unfair pricing practices.

2.Vertical M&A

Vertical M&A involves two companies that are not competitors but are in the same industry. They are more likely to produce goods or services for the same product but are in different stages within an industry’s supply chain.

For example, if a car company acquired another company that supplied seatbelts for its cars, that would be a vertical merger and acquisition. The goal is to control more stages of the production and distribution process, which can lead to cost reductions.

3. Concentric M&A

Concentric M&A involves two businesses that have the same customers in a specific industry but they offer different products and services. An example would be a cell phone company merging with a cell phone case company.

4. Conglomerate M&A

This type of M&A involves combining two companies that have unrelated business activities. Conglomerate mergers are typically done to expand into other industries.

5. Product Extension M&A

A product extension M&A is a type of transaction in which companies sell different but related products in the same market. For instance, a pencil manufacturer might merge with a company that produces erasers. The goal is to diversify products and offer more to the same customer base.

6. Market Extension M&A

This type of M&A involves two companies that sell the same products but are in separate markets. A market extension merger is typically undertaken to expand geographical reach and gain access to a larger customer base.

An example is a company in the United States merging with a company in Europe to gain access to each other's markets. This cross-border deal enables the acquirer to capitalize on new market opportunities and drive international growth.

7. Bolt-On Acquisitions

This type of acquisition usually involves a larger company buying a small business to expand its existing business segment and enhance its existing operations. In this strategy, the smaller company may retain its name and identity.

8. Tuck-In Acquisitions

Tuck-ins are very similar to bolt-ons, with one major difference. The buyer completely absorbs the small business, losing its corporate identity.

9. Roll-Ups Acquisitions

The roll-up strategy is a specific type of acquisition strategy in which a company, typically a private equity firm, acquires multiple smaller companies in the same market and merges them into a new legal entity, thereby forming a single, larger entity. It is also known as consolidation. The goal is to form a dominant entity in a highly fragmented market.

10. Hostile Takeover

Despite popular belief, not all acquisitions are mutual. Hostile takeovers are a type of acquisition in which the acquirer forces the target company to sell against its will. This is only possible if the target business is a public company.

Read our article on examples of hostile takeovers.

11. Capability Acquisitions

This strategy is extremely popular in industries where technological advancement and specialized skills are pivotal. A capability acquisition is when a company acquires another company specifically for its capabilities that it does not possess. These capabilities can include new technologies, intellectual property, or operational processes.

12. Acquihire

Acquihire is a strategy that primarily focuses on acquiring a company's stakeholders or employees. This strategy is extremely common in the tech industry, where the competition for talented engineers, developers, and leaders is intense.

The table below breaks down the various types of M&A strategies, their primary purpose, how they impact ownership, and examples or use cases.

Why Companies Go for Mergers and Acquisitions

Before the M&A process begins, key executives, including those on the board of directors, consider numerous factors. But in a nutshell, the motives for mergers and acquisitions tend to fall under one of the following:

1. Synergies

Synergies describe the extra value generated when two companies combine, or simply put, “one plus one equals three.” This occurs when a resource, such as capital or intellectual property, is shared between the two firms in the new entity, allowing both companies to benefit from the resource instead of just one. There are two types of synergies:

a. Cost synergies – These are cost reductions incurred from combining the two entities. The most common example of this is economies of scale. Larger volumes will result in better discounts from suppliers.

b. Revenue synergies—These are additional sales or revenue that the combined entity will generate. The most common example is cross-selling to both companies' customers.

2. Expansion

M&A is a terrific way to enter new markets, expand geographic reach, and achieve product portfolio diversification. Instead of building these things from scratch, acquiring another company will instantly produce these goals while generating revenue.

Consider a U.S. company seeking to enter the Asian market. Starting a business from scratch in a foreign country can be a more challenging process than acquiring an existing Asian company with an established presence in the target market.

3. Defensive Play

Defensive play simply means a company buying its competitors. Buying the competition will increase its market share while eliminating potential future threats. This is extremely common for large companies facing startups.

One of the most famous M&A examples is Google's acquisition of YouTube in November 2006. YouTube was a fast-growing video-sharing platform starting to draw significant online traffic. Google saw this as a threat to its digital advertising market and decided to buy it for $1.65 billion.

This strategic move allowed Google to protect its advertising revenue and expand its presence in the online video market.

4. Capability

There are also instances where the acquiring company makes acquisitions to gain certain capabilities and enhance its existing operations. A notable example of this is Amazon's 2012 acquisition of Kiva Systems, a company specializing in automation technology for warehouse management and fulfillment centers.

Amazon acquired them for $775 million to streamline its warehouse operations, reduce shipping times, and decrease costs through advanced robotics and automation technology.

5. Tax Benefits

Tax benefits are also a motivator for some companies to engage in mergers and acquisitions. By combining businesses, companies can often utilize tax laws to their advantage and reduce their overall tax burden. For instance, if a company acquires another business that has been losing money, those losses can be used by the new owner to reduce future tax liabilities.

How Do Companies Finance Mergers and Acquisitions?

1. Cash

Cash is the most straightforward method for financing M&A deals. Using the company's cash reserves, the buyer pays the seller a specific amount in exchange for the company's ownership. This method is most appealing to the sellers because it offers immediate payment.

On the other hand, the acquiring company would want to hold on to their cash for as long as possible, unless interest rates are too high.

2. Debt Financing

Debt financing involves companies borrowing funds through bank loans, bonds, and other forms of debt to cover the costs of the transaction. They have several options for sources, including commercial and investment banking, private equity firms, and other financial institutions.

If interest rates are low, debt financing would be the company’s first option for utilizing its cash reserves in other investments and maximizing opportunities.

3. Seller Financing

There are also instances where the seller agrees to finance the transaction on behalf of the buyer. In short, the seller agrees to deferred payment in exchange for a slightly higher purchase price. This type of transaction requires a lot of trust between the buyer and seller.

4. Stock Payments

In this scenario, the buyer pays the seller using their company’s shares. This allows the buyer to acquire the target company without using cash or leveraging their balance sheet. This method can also be attractive to the seller if the acquirer’s stock has a high value and is expected to perform even better after the acquisition.

5. Earnouts

Whether it's used as a financing strategy or to bridge valuation gaps, earnouts simply mean the buyer agrees to pay a certain amount upfront and then additional payments based on the future performance of the business sold.

For instance, the seller is asking for $150 million for their company, and would not negotiate for anything less. The buyer can now employ an earn-out and agree to pay $120 million upfront, with the remaining $30 million subject to future performance.

6. Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

A buyout is the term for when an investor (typically a private equity firm) purchases the majority stake in a company, with the goal of taking over its decision-making process or changing its strategy to boost performance. What makes a leveraged buyout unique is that the buyer uses debt instead of equity to pay for the acquisition.

The investor uses the target company’s assets to secure the loans, and thus the target’s future cash flows to service the debt. In exchange, the buyer only puts down a small amount of equity. This enables firms to acquire control of other companies without incurring significant capital.

The high debt can also result in outsized returns on the small amount of capital at risk if the company performs well after the acquisition. KKR's buyout of RJR Nabisco is a classic example of an LBO: high leverage, high risk, and high potential returns.

7. Mezzanine Financing

Mezzanine financing is a source of capital between senior debt (the first layer of financing used to finance an acquisition) and equity in the deal. It's used to bridge the gap when a traditional loan isn't enough for the purchase price, enabling buyers to close the acquisition without additional equity. It’s treated like debt but may give the lender an equity interest if the borrower can't repay.

Due to its riskier position compared to senior debt, mezzanine financing has higher interest rates. However, it is popular in M&A transactions due to its ability to bridge funding gaps without immediate ownership dilution.

8. Asset-Based Financing

In asset-based financing, the buyer borrows money secured by the target company’s assets. The assets used as collateral can include equipment, inventory, receivables, or real estate. The maximum amount that can be borrowed depends on the quality and value of the assets in question.

Asset-based financing can be especially helpful in the acquisition of an asset-heavy company, such as a manufacturer, logistics company, or retailer, where the quality of assets provides a safety net and low risk for lenders.

The table below breaks down the types of M&A financing methods, how they work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Legal & Regulatory Considerations

All M&A transactions, regardless of size or sector, are subject to legal and regulatory scrutiny. In fact, part of the legal due diligence process requires advisors and attorneys to look at the corporate structure, contracts, intellectual property, labor and employment agreements, tax exposure, environmental liabilities, and existing debt and finance agreements in order to uncover any red flags that may impact negotiations, purchase price, or the overall viability of the deal.

National and international regulators also scrutinize mergers and acquisitions. In the United States, for instance, larger transactions typically require a Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filing with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) for antitrust review. Foreign investment transactions may also be subject to a review by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) on national security grounds.

In the European Union, transactions must be cleared with the EU Commission if they are expected to impact competition and may need to be GDPR compliant if personal data is transferred. Similar procedures are followed by antitrust and competition authorities in the UK, Canada, India, China, and other major jurisdictions.

Lawyers involved in an M&A transaction are typically responsible for its legal structure, drafting and negotiating purchase agreements, preparing and filing regulatory paperwork, and ensuring compliance with securities laws.

If the transaction spans multiple jurisdictions and/or involves sensitive industries such as healthcare, defense, and financial services, or public companies, the role of legal advisors becomes even more crucial. Thorough legal due diligence can help avoid post-closing lawsuits, integration issues, and regulatory fines or penalties, making it one of the most important phases of an acquisition.

M&A Process Explained

To understand the M&A process, it’s helpful to understand both the buy-side and sell-side M&A process.

Sell-Side M&A Process Steps

- Establish a motive for sale

- Ensure that your company is ‘sale ready’

- Create DealRoom for the company materials and due diligence process

- Create a long list of potential buyers

- Develop a Confidential Information Memorandum (CIM)

- Signing the Letter of Intent (LOI)

- Be ready for confirmatory due diligence

- Negotiate with buyers

- Signing and Closing

Buy-Side M&A Process

- Develop an M&A Strategy

- Develop a search criteria

- Develop a long list of companies for acquisition

- Contact target companies

- Preliminary due diligence

- Negotiations

- Letter of Intent

- Confirmatory Due Diligence

- Signing and Closing

- Integration

Real-World M&A Examples (with Lessons Learned)

One of the quickest ways to learn what makes an acquisition succeed (or fail) is to study previous deals. Here are some examples, grouped by outcome, highlighting what worked or what went wrong.

Successful Deals: Synergy & Strategic Fit

- Disney-Pixar (2006): Disney acquired Pixar for $7.4 billion for its technology and creative culture. Disney afforded Pixar creative independence in exchange for distribution and merchandising muscle. Following the acquisition, Disney’s animation revenue doubled in three years. New franchise opportunities have driven the company's growth for decades.

- Facebook-Instagram (2012): Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 billion, when the company had only 13 employees. Instead of integrating and diluting the platform, Facebook allowed it to grow autonomously while adding advertising capabilities and infrastructure. Today, Instagram generates nearly $67 billion in annual revenue (and accounting for nearly 40% of Facebook’s total revenue), far exceeding its purchase price.

The key takeaway from these and other successful M&A deals is that strategic fit, synergy, and respect for the acquired company’s culture are what create value.

Deal Failures: Culture & Execution Breakdowns

- AOL-Time Warner (2000): In a $165 billion merger, leaders of both companies believed traditional media and internet distribution could combine seamlessly. However, cultures clashed, expectations were misaligned, and the dot-com bubble burst, resulting in the destruction of over $200 billion in value.

- Daimler-Chrysler (1998): While it was branded as a “merger of equals,” Daimler viewed Chrysler as a subsidiary. Misaligned values, conflicting leadership, and geographic differences led to poor collaboration and declining sales. Daimler sold Chrysler less than a decade after the merger.

The key takeaway from these failed M&A deals is that culture, leadership alignment, and integration planning are as important as financial logic.

These examples also highlight why tools like DealRoom’s M&A Platform exist: to prevent failures due to poor due diligence or integration.

M&A Risks & Challenges

M&A failures are typically not due to one big mistake but a series of miscalculations, including strategic, cultural, financial, and execution errors. Identifying risks early on can help M&A teams plan more pragmatically and sidestep foreseeable challenges.

Overvaluation and Bad Assumptions

Buyers often pay too much based on overly aggressive revenue forecasts or unrealistic synergy expectations that fail to materialize. Overconfidence, bidding wars, and the pressure to deploy capital may drive valuations above what a company can deliver post-acquisition.

Cultural Misalignment

Perfectly sound deals can fall apart due to differing work cultures. A clash in leadership style, communication practices, decision-making speed, or employee values can cause internal strife and talent loss (e.g., Daimler-Chrysler).

Integration Complexity

Integration of IT systems, processes, legal entities, and teams is more challenging than most projections anticipate. Without a well-defined and effectively executed post-merger integration (PMI) plan that encompasses HR, finance, IT, sales, and operations, anticipated synergies are often delayed or lost. This is where using a tool like DealRoom’s M&A Platform can help to keep workstreams aligned and on time.

Regulatory and Legal Roadblocks

Antitrust issues, national security reviews (e.g., CFIUS in the U.S.), industry-specific regulations, or international legal discrepancies can delay or derail a transaction. Lengthy regulatory processes increase transaction costs and uncertainty, and mandatory divestitures can alter the deal’s structure.

Debt Burden and Financial Risk

In leveraged transactions, excessive debt levels put pressure on cash flows. If the business experiences a downturn in revenue or if synergies do not materialize as quickly as expected, the company might face difficulties in servicing its debt, potentially leading to restructuring or bankruptcy.

Employee Uncertainty and Customer Disruption

Unclear communication during a deal can lead to employee churn, lower morale, and customer attrition, while competitors are poised to capitalize on the disruption to poach clients or talent.

Most risks don’t materialize after the deal; they’re built in from the beginning, when strategy, valuation, and integration planning are still being developed. Teams that plan for these challenges upfront and treat integration as part of the deal, rather than an afterthought, are the ones that win and capture value time and time again.

Key Takeaways

- Nearly every billion-dollar company has participated in mergers or acquisitions, making M&A one of the most impactful strategic actions businesses take to grow, expand into new markets, or gain competitive advantages.

- M&A encompasses mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, strategic alliances, and more specialized strategies, such as bolt-ons or roll-ups, each designed to achieve specific outcomes, including synergies, market expansion, or capability gains.

- Most M&A failures stem from cultural clashes, poor post-merger integration, or overvaluation, which is why meticulous due diligence and structured integration planning are critical to capturing long-term value.

DealRoom’s M&A Platform offers due diligence and project management capabilities designed to address the many challenges in M&A. It should be considered a critical element of the process by any company undertaking agile M&A.

Get your M&A process in order. Use DealRoom as a single source of truth and align your team.

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)