Is a merger of equals possible?

This question usually follows a discussion about the nature of deals between companies of similar size and what drives them.

The answer is that yes, mergers of equals do exist, and in this article, we provide an overview of how this type of deal works and the challenges they bring

What is a Merger of Equals?

As the name suggests, a merger of equals occurs when two companies of roughly equal size merge to create a new company. When the merger closes, shareholders from each of the companies receive shares in the newly formed company in exchange for the shares that they held in the two companies that made the merger. In the case of the merger of equals, the shares received by both parties will be close to parity, making them ‘equals’ in the merger.

How does a Merger of Equals work?

Mergers of equals are relatively uncommon, with the thinking being that company managers are reluctant to give up their own power, even if it means creating a company for shareholders that is almost twice the size of the current company.

For a deal to happen, one company’s CEO is almost certainly going to have to give up his or her position (Co-CEOs, like the ones Goldman Sachs has had, are uncommon), and suddenly the deal doesn’t seem so equal anymore.

If this barrier can be overcome, it’s important to look at the valuation.

Remember that just because two companies operate in the same industry, have the same geography, and have almost identical target markets, they may have different values and growth prospects.

Those involved in structuring the deal need to consider these differences objectively, without becoming a prisoner to the ‘merger of equals’ label attributed to the deal.

When the two companies have been valued–and both parties have agreed to their own valuation and that of the other company–the NewCo is based on the consolidated financial statements of both companies. The shares are typically divided on a pro-rata basis in the new company (e.g., if the valuations showed that one company was worth 5% more than the other, its shareholders will receive 5% more shares).

Having agreed to the structure in the new company (management level changes, changes to branding, marketing and sales, etc.), the newly formed company should (in theory) be able to enjoy the benefits of scale that come with doubling a company’s size in a short period of time.

And, of course, as a merger of equals, there are sure to be several revenue synergies achieved by the newly formed company.

Challenges in Mergers of Equals

The previous section gave a somewhat prosaic version of how mergers of equals happen. In reality, true mergers of equals are uncommon because of the challenges that they bring, principally in management.

Here are just some examples of the challenges faced:

The agency challenge

The relative rarity of mergers of equals suggests that managers are often looking out for themselves rather than their shareholders. A merger of equals would demand that one CEO give up their position to the other, despite managing a virtually identical company.

“Everyone wins except me,” says the disgruntled CEO, who then passes up the opportunity.

The organizational structure challenge

The issue of who takes the CEO role can be repeated all the way down the organizational chain. Who takes the CFO role if there are two CFOs? Who's the head of strategy? It’s not that these issues aren’t common in every large M&A transaction, but they tend to dog mergers of equals more, with many involved in the deal feeling the spirit of the deal isn’t reflected in the outcomes.

The antitrust challenge

When two companies are of equal standing and competing ferociously, the customer tends to benefit more. When they come together, the opposite is the case. This tends to be truer as their market share increases.

Thus, the antitrust commission often takes a very skeptical view of ‘mergers of equals’ for this reason.

The culture challenge

When a large company acquires a small company, it’s generally quite clear whose culture is going to be pervasive after the deal.

But when two companies of equal size–perhaps with remarkably different corporate cultures–come together, who is going to yield? Small issues around the office suddenly become deal breakers and the moniker ‘merger of equals’ can even tend to drag down the deal rather than act as a catalyst for it.

Understanding the process of Merger of Equals

We’ve described the general way a merger of equals works, but let’s get into the actual step-by-step process to help you understand what it really involves. While this may not align with absolutely every case, the following steps should capture the most important aspects of the process.

Step 1: Initial planning and discussions

As a first step, leaders at the two companies will need to meet to discuss the strategic benefits of a possible merger. This will likely involve a close look at each other's' finances, an assessment of how compatible their company cultures are, ways in which their strengths may compliment each other, any weakness the other should know about, and much more. Because nothing has been agreed to at this juncture, everything at this stage should be kept strictly confidential.

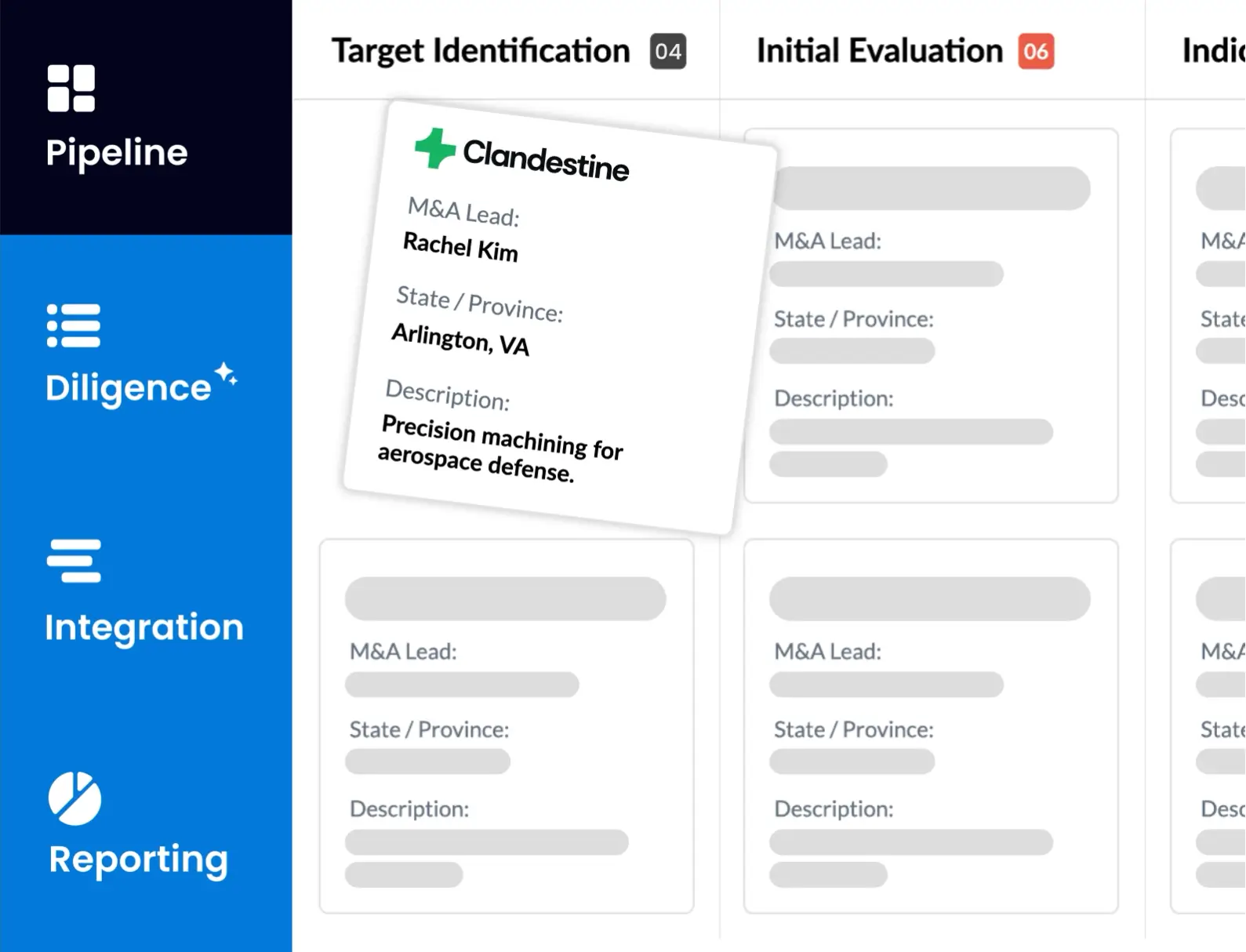

Step 2: Conducting due diligence

If management at both companies wants to proceed, the next step is to undertake a more thorough financial and operational review. Both companies will probably want to hire professional advisors to look at income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow to verify each other’s value. They’ll also want to assess each other’s supply chains and intellectual property, examine any pending lawsuits or regulatory concerns, and look at how their management styles and organizational culture align.

Step 3: Determining valuation

Next, it’s time to determine the value of each company prior to any possible merger. This is typically done by an investment bank. While there are many methods, common types of analyses include the following:

- Discounted cash flow (DCF): This method determines value based on expected future cash flows. If DCF is higher than the current cost of investment, then the opportunity will likely be positive.

- Comparable company analysis: This method determines value based on a comparison of similar sized businesses in the same industry. A high ratio means the business is overvalued, while a low ratio means it is undervalued.

- Precedent transactions: This method determines value based on the past performance results of the company. This kind of analysis can be difficult since previous market conditions can vary.

Once the value of each company has been set, the share exchange ratio is calculated. As this is a merger of equals, this ratio should be close to 1:1, although it may vary slightly.

Step 4: Negotiating the deal

This is where the details have to be worked out. Representatives from both companies will have to agree on a number of items, such as how the leadership team will be composed, how many board members the new company will have (and who they will be), what the new company’s brand and identity will look like, whether its headquarters will need to move, and much more.

Step 5: Drafting the merger agreement

With the deal negotiated and the terms agreed on, a legal merger agreement will have to be written up and signed. This should outline details such as the tax structure of the merger, how governance will function within the new company, and what will happen if one party wants to walk away.

Step 6: Getting regulatory approval

Many potential mergers can get held up or canceled altogether if they run into regulatory hurdles. For this reason, it’s important that the companies proceed with caution in order to get approval from regulatory bodies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and Department of Justice (DOJ).

Step 7: Getting shareholder approval

Hopefully by this stage, shareholder support has already been shored up. Regardless, both companies will need to call a special shareholder meeting and hold a vote on the proposed merger. If a majority approve of it, then it can continue. If not, then it might be back to the drawing board.

Step 8: Communicating to customers and employees

Once shareholder and regulatory approvals have been reached, it’s time to make a public announcement of the merger. This should start with both companies’ customers and employees. They should get all the details regarding how the merger will impact them. Employees will want to know how their roles will change, while customers will want to know what will happen to their product or service.

Step 9: Planning out the integration

With everyone informed and the deal all but done, it’s important to put together teams from both companies to manage how everything will be combined into one entity. This will include company operations, IT systems, human resources and other functions, as well as cultural integration.

Step 10: Finalizing the deal

At last, once everything is in place, the merger agreement can be executed and the shares can be exchanged according to the terms of the deal. Afterwards, the new company can begin its operations.

Team composition under the merger of equals

One of the biggest challenges when two equal companies merge is how they should best organize their teams. This can be particularly difficult when it comes to executives, who may not be eager to step away from their positions or work beneath someone else. Because of this, it is common for executives from both companies to make up the leadership team in the new entity.

In some cases, this may involve them sharing responsibilities or jurisdictions, while in others it may require new roles to be created. Usually, there will be a period of adjustment in which the company can see how all this works out. Some of these new roles may become essential. Other leaders may find that they don’t mind sharing workloads with other executives. However, in order to avoid redundancy and inefficiency, it may become necessary to select the executives who are the best fit.

What about the CEO? Determining who will lead the new company can be a contentious issue. There are several ways this can play out:

- Split CEOs: In this arrangement, the CEOs both retain their positions but agree to divide up responsibilities. While this is fairly common at the beginning of a MOE, it can be tricky to successfully pull off long-term. It will require a lot of communication and a willingness to work toward the larger good of the company.

- Single CEO: If it can be agreed on ahead of time, choosing one CEO to lead the company can be the simplest approach. However, if neither CEO wants to give up their role, the selection may have to come down to a decision that must be made by the board, shareholders, or even employees.

- Advisory CEO: Halfway between a pure power-sharing agreement and a single CEO, an advisory CEO can play a smaller but important role in helping ensure the success of the primary CEO. This can be either a temporary position or a permanent one, depending on the circumstances of the company.

Board of directors under the merger of equals

Figuring out the new composition of the board of directors can also be difficult. Issues that will have to be agreed on include the size of the new board, whether former board members will join the new board, and whether any new members should be selected.

Ideally, the size and composition of the board can be worked out during the planning phase. For instance, it is common for many companies undergoing a MOE process to simply allocate board seats in proportion to each company’s pro forma ownership percentage: If one company is given 51 percent of shares and the other 49 percent, then the board would be split in such a way as well.

However, if there are disagreements over board size or composition, there may be a need to come up with creative solutions. This could include requiring that certain decisions can only be made with a supermajority board vote, rotating the chair every few months, and giving one company the chair role of multiple sub-committees.

In the end, the ultimate goal is for both sides to come to an agreement and begin operating as one.

Impact of merger of equals

The purpose of a merger of equals is to create a new company that is more valuable than what the individual companies could independently achieve. In other words, as it is often described, you want to make one plus one equal three.

But doing this successfully requires that the combined entity create efficiencies that neither of the smaller companies have. By combining their different businesses, technology, IP, and expertise, the new company should be able to operate in a more streamlined fashion that both reduces costs and generates increased revenue.

That is the hope, but of course it will take a good deal of planning and preparation to pull this off. There may even be a several months-long period after which the MOE is first announced when it may look unlikely that the two companies can successfully combine forces. During this time, other companies or investors may try to make a cash acquisition instead. This will make it imperative that the original reasons of the MOE and the returns it is expected to produce are clearly and consistently communicated to the shareholders so that they are not tempted by any hostile takeovers.

If all this is executed well, then the shareholders of both companies will benefit once the MOE goes through.

Example of a Merger of Equals

The merger between the banking industry giants Citi and Travelers in 1998 is a textbook example of a merger of equals.

Shareholders of each of the two companies agreed to divide the shares in the new company–which became Citibank–almost equally between them.

Furthermore, management adopted a ‘Noah’s ark’ strategy when composing the new management team. Every top management position was in two: two CEOs, two COOs, etc. The board was divided evenly between the former employees of Citi and Travelers.

In some respects, the deal was an undoubted success: In the 18 months after the deal closed, net profits increased from around $6 billion (achieved by combining the net profit of both Citi and Travelers before the transaction) to just under $10 billion.

And in the age before fintech, the newly formed Citibank was the first bank to offer its retail and corporate clients every financial product under the sun. Its status as the world’s largest bank by market cap ($84 billion after the deal was announced) also gave it considerable power in global markets.

Conclusion

The terminology in M&A can often be overemphasized at the expense of good practice. Mergers of equals are a case in point. Students commonly argue: “if two companies can never be identical, how can they be equal?”

It’s a fair question, but an academic one.

The M&A Science Academy includes a range of courses and podcasts that cover this and several other questions like it while emphasizing the importance of strong M&A practice rather than theory alone. The academy is designed for anybody that wants to take their M&A practice to the next level.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.avif)